Tag: evolution of law

Family Tree of Languages Has Roots in Anatolia, Biologists Say {via NY Times}

(1) Kinda amazing – the NY Times decided to have the public chew on a dendrogram – pretty damn cool 🙂

(1) Kinda amazing – the NY Times decided to have the public chew on a dendrogram – pretty damn cool 🙂

(2) Among other reasons, I also post this because this topic is of great import to the ungoing study of the origins of Western Civilization and Western Legal Thought. In particular, this is part of an important active conversation in the legal academy community – (see e.g. Rob Kar’s paper On the Origins of Western Law and Western Civilization (in the Indus Valley). Also, check out – The Early Eastern Origins of Western Law and Western Civilization: New Arguments for a Changed Understanding of Our Earliest Legal and Cultural Origins – Part I, Part II and Part III. They are a real tour de force!

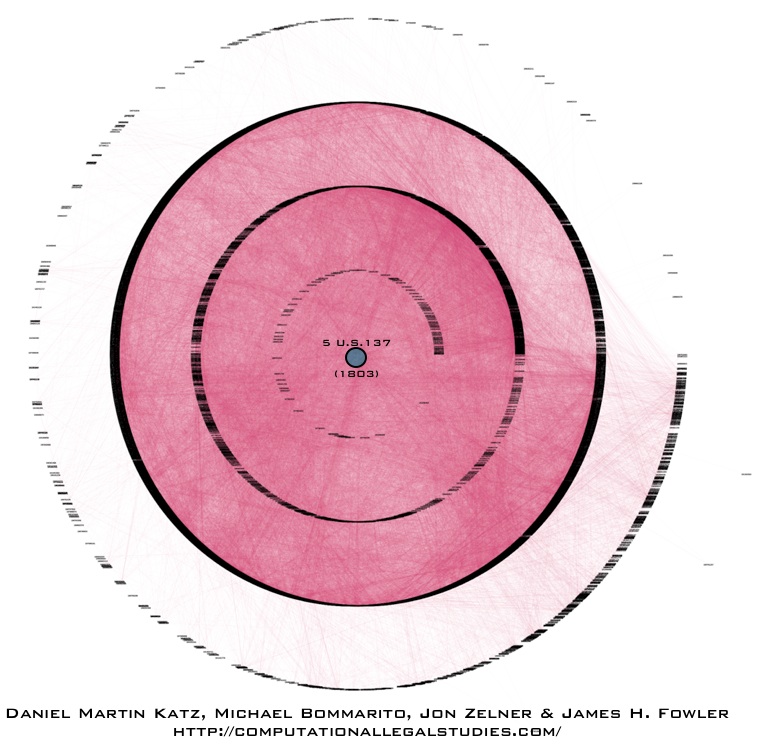

Six Degrees of Marbury v. Madison : A Sink Based Visualization [v2]

The visualization above is something we are calling the “six degrees” of Marbury v. Madison. It was originally produced for use in our paper Distance Measures for Dynamic Citation Networks. Due to space considerations, we ended up leaving it on the cutting room floor. However, the visual is designed to highlight the idea of a “sink.”

Sinks are one of the core concepts which we outline in Distance Measures for Dynamic Citation Networks, 389 Physica A 4201 (October 1 2010). Looking through the prism of a citation network, sinks are the root to which a given legal concept, academic idea or patent based innovation can be drawn. From each citation in a non-sink node, it is possible to trace the chains of citations back to their root (which we call a sink). In the visualization above, the root or sink node is the famed United States Supreme Court decision Marbury v. Madison. Starting from the center and working out to the edge, the first ring are cases that directly cite Marbury v. Madison. The next ring are cases which cite cases that cite Marbury v. Madison. The next ring are cases which cite cases which cases that cite Marbury v. Madison and so on…

Anyway, one of the major contributions of our Distance Measures for Dynamic Citation Networks paper is that it allows us to use these sinks to create pairwise distance/similarity measure between the ith and jth unit. In this instance, the units in this directed acyclic network are the ith and jth decisions of the United States Supreme Court.

Now, it is important to note cases contain many citations and thus can be oriented relative to many different sinks. So, even if a case can be traced to the Marbury sink – this does not preclude it from being traced to other sinks as well. Also, it is possible to construct a variety of mathematical functions to characterize the sink based distance between units. For instance, the importance of a sink might decay as its shortest path length increases. An alternative measure might weight the importance of each sinks by the number of unique ancestors shared between nodes i and j that are descended from a given sink of interest. Indeed, many fine-grained choices are possible but they require justification drawn from the given substantive problem.

As mentioned above, this method has potential applications including tracing the spread of technological innovation in patent citations or the spread of ideas in a set of academic articles. However, given our primary interest surrounds the judicial citations, we are working on the follow up to the “sinks” paper. In this follow up paper, we hope to carry these and other ideas forward into a definitive community detection method for judicial citation networks.

To preview, at least two major dynamics must be considered in any null model for community detection. First, case-to-case citations can help contribute to the fractal nature of legal systems. In other words, we are pretty far from any sort of gaussian null model. However, this is easy enough to confront with an alternative null — some highly skewed distribution (i.e. power law or power law with a cutoff, etc.)

Here is the difficult part — the cross fertilization of legal concepts. This is a time evolving network where ideas are referenced/imported from otherwise unrelated or previously unrelated domains. The examples of cross-fertilization are numerous. One of my personal favorite non-SCOTUS examples is the use of the tort doctrine of “trespass to chattels” in the context of web scraping.

Here is the difficult part — the cross fertilization of legal concepts. This is a time evolving network where ideas are referenced/imported from otherwise unrelated or previously unrelated domains. The examples of cross-fertilization are numerous. One of my personal favorite non-SCOTUS examples is the use of the tort doctrine of “trespass to chattels” in the context of web scraping.

Anyway, we hope to have more to come on the topic of SCOTUS community detection in the weeks and months to come. In the meantime, please check out a Dynamic 3D Hi Definition United States Supreme Court Visualization.

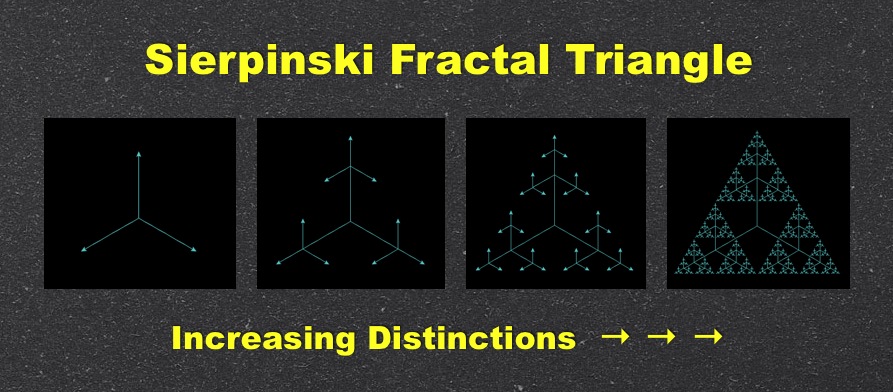

How Long is the Coastline of the Law: Additional Thoughts on the Fractal Nature of Legal Systems

Do legal systems have physical properties? Considered in the aggregate, do the distinctions upon distinctions developed by common law judges self-organize in a manner that can be said to have definable physical property (at least at a broad level of abstraction)? The answer might lie in fractal geometry.

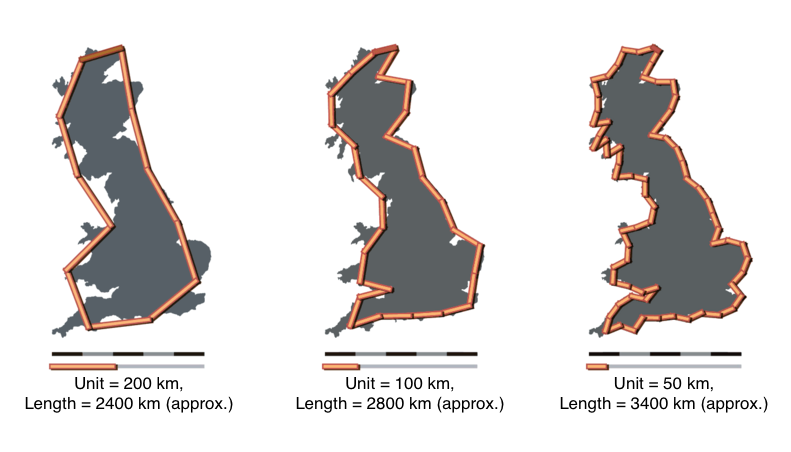

Fractal geometry was developed in a set of classic papers by mathematician Benoît Mandelbrot. The original paper in the field How Long is the Coastline of Britain describes the coastline measurement problem. In short form, the length of the coast line is a function of the size of measurement one employs. As shown below, as the unit of measurement decreases the length of the coastline increases. The ideas expressed in this and subsequent papers have been applied to a wide class of substantive questions. In particular, the application to economic systems has been particularly illuminating. Given recent economic events, we agree with views of the Everyday Economist arguing the applied economic theory built upon his work should earn Mandelbrot a share of the Nobel Prize.

A more abstract fractal is the simple version of the Sierpinski triangle displayed at the top of this post. Here, there exists self similarity at all levels. Specifically, at each iteration of the model, the triangles at the tip of each of the lines replicate into self similar versions of the original triangle. If you click on the visual above, you can run the applet (provided you have java installed on your computer). {Side note: those of you NKS Wolfram fans out there will know the Sierpinski triangle can be generated using cellular automata Rule 90.}

A more abstract fractal is the simple version of the Sierpinski triangle displayed at the top of this post. Here, there exists self similarity at all levels. Specifically, at each iteration of the model, the triangles at the tip of each of the lines replicate into self similar versions of the original triangle. If you click on the visual above, you can run the applet (provided you have java installed on your computer). {Side note: those of you NKS Wolfram fans out there will know the Sierpinski triangle can be generated using cellular automata Rule 90.}

For those who are interested in another demonstration consider the Koch Snowflake — a fractal which also offers a view of the relevant properties. The Koch Snowflake is a curve with infinite length (i.e. there is no convergence even though it is located in a bounded region around the original triangle). Click here to view an online demo of the Koch Snowflake.

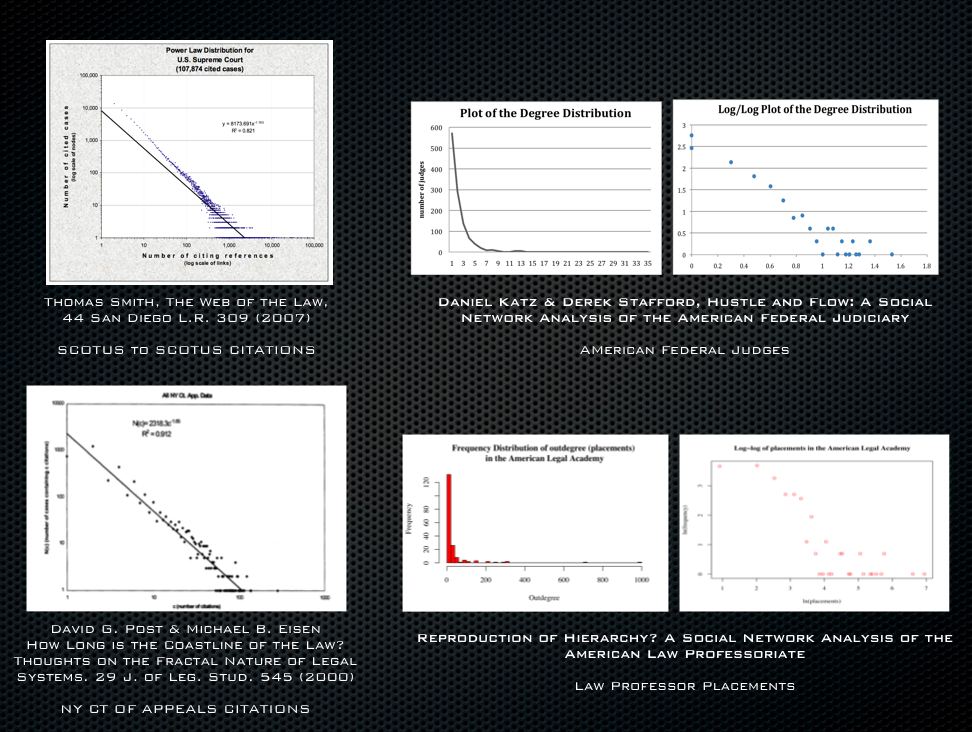

So, you might be wondering … what is the law analog to fractals? As a first-order description of one important dynamic of the common law, we believe significant progress can be made by considering the conditions under which legal systems behave in a manner similar to fractals. For those interested, a number of important papers have discussed the fractal nature of legal systems. While discussing legal argumentation, the original idea is outlined in two important early papers The Crystalline Structure of Legal Thought and The Promise of Legal Semiotics both by Jack Balkin. The empirical case began more than ten years ago in the important paper How Long is the Coastline of the Law? Thoughts on the Fractal Nature of Legal Systems by David G. Post & Michael B. Eisen. It continues in more recent scholarship such as The Web of the Law by Thomas Smith.

In our view, the utility of this research is not to adjudicate the common law to be a fractal. Indeed, there exist mechanisms which likely prevent legal systems from actually behaving as unbounded fractal. The purpose of the discussion is determine whether describing law as a fractal is a reasonable first-order description of at least one dynamic within this complex adaptive system. While full adjudication of these questions is still an area of active research, we highlight these ideas for their important potential contribution to positive legal theory.

One thing we want to flag is the important relationship between the power law distributions we discussed in these prior posts (here and here) and the original work of Benoît Mandelbrot. The mapping of the power law like properties displayed by the common law and its constitutive institutions is part of the larger empirical case for the fractal nature of legal systems. Building upon the prior work, in two recent papers, which are available on SSRN here and here, we mapped this property of self organization among two sets of legal elites — judges and law professors.

Computational Legal Studies Presentation Slides from the Law.gov Meetings

Thanks to Carl Malamud and the good folks at the University of Colorado Law School and University of Texas Law School for allowing us to participate in their respective law.gov meetings. For those interested in governmental transparency, we believe that Carl Malamud’s on-going national conversation is very important. The video above represents a fixed spaced movie combining the majority of the slides we presented at the two meetings. If the video will not load, click here to access the YouTube Version of the Slides. Enjoy!

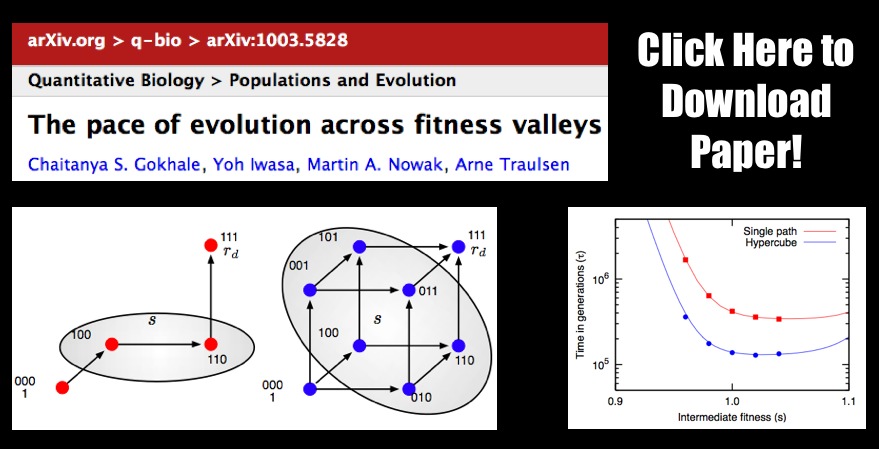

The Pace of Evolution Across Fitness Valleys

From the abstract: “How fast does a population evolve from one fitness peak to another? We study the dynamics of evolving, asexually reproducing populations in which a certain number of mutations jointly confer a fitness advantage. We consider the time until a population has evolved from one fitness peak to another one with a higher fitness. The order of mutations can either be fixed or random. If the order of mutations is fixed, then the population follows a metaphorical ridge, a single path. If the order of mutations is arbitrary, then there are many ways to evolve to the higher fitness state. We address the time required for fixation in such scenarios and study how it is affected by the order of mutations, the population size, the fitness values and the mutation rate.”

SEAL 11 @ William & Mary Law School

This weekend we participated in the Society for Evolutionary Analysis in Law (SEAL) annual meeting at William & Mary Law School. For those not already familiar, SEAL is devoted to the integration of the life sciences and social sciences into legal scholarship and teaching. Relevant topics include but are not limited to evolutionary and behavioral biology, cognitive science, complex adaptive systems, economics, evolutionary psychology, primatology, etc. SEAL boasts over 400 members from 30 countries — including the 2009 Economics Nobelist Elinor Ostrom. Anyway, this weekend witnessed a very interesting and exciting set of presentations …. we are looking forward to more great presentations at SEAL 12.

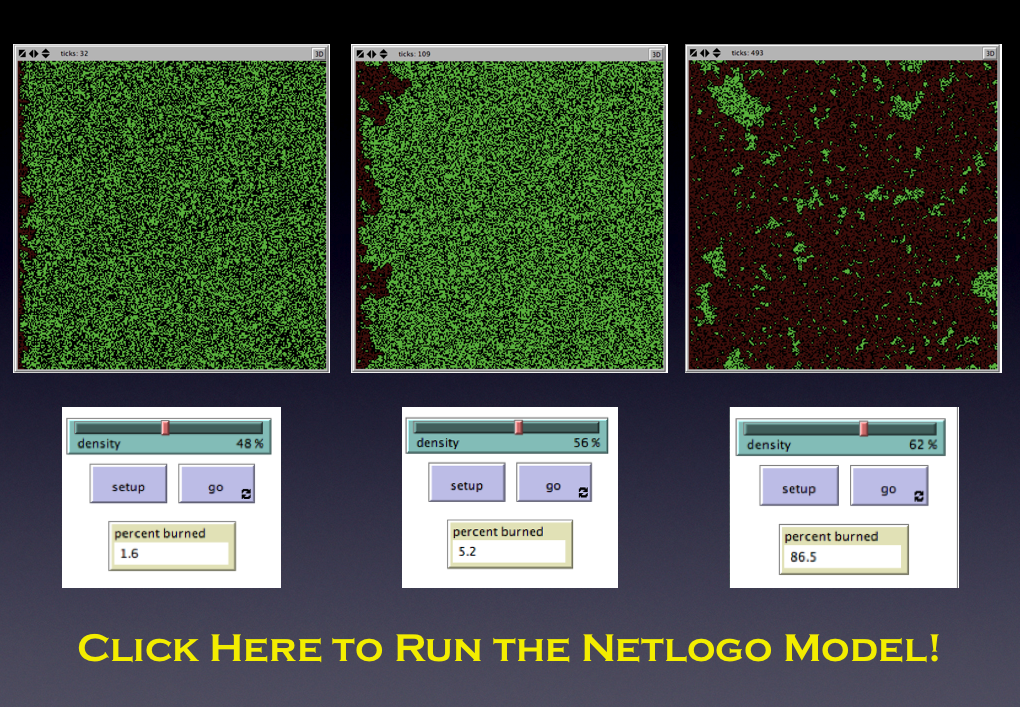

Forest Fire Model-A Popular Example of Non-Linearity [Repost from 5/13]

The Forest Fire Model is a commonly invoked example of non-linear system–where a very small perturbation can generate significant differences in observed outcomes. Consider the above Netlogo–to Run the Model: (1) Adjust the Density Slider to set the concentration within the Forest. (2) Hit the Setup Button (3) Hit the Go Button …. Rinse and Repeat at different levels of Density.

Above is the output for a run of the model at several levels of Density {48%, 56%, 62%}. Notice the differences in the Percent Burned {1.6%, 5.2%, 86.5%}.

This is obviously a theoretical model but it has potential application to a wide class of substantive questions including regulatory failure. In addition, the Forest Fire Model is important because it has been invoked in the critique of the popular book The Tipping Point. Specifically, in discussing the book network scientist Duncan Watts notes “It sort of sounds cool … But it’s wonderfully persuasive only for as long as you don’t think about it.” Watts notes “…trends are more like forest fires: There are thousands a year, but only a few become roaring monsters. That’s because in those rare situations, the landscape was ripe: sparse rain, dry woods, badly equipped fire departments. If these conditions exist, any old match will do…. and nobody… will go around talking about the exceptional properties of the spark that started the fire.” (Quotes from Jan 2008 Is the Tipping Point Toast? Fast Company Magazine).

Power Laws, Preferential Attachment and Positive Legal Theory [Part 2] [Repost]

As was stated in Part 1 of this thread, it is by no means a given that the statistical artifact displayed above would appear. Namely, such large scale patterns need not assume this flavor as many social and physical systems feature substantially different properties.

For purpose of generating an empirically grounded theory of American Common Law development … explaining these artifacts would seem to critical. Fortunately, with respect to the above pattern, there exist a definable set of generative processes plausibly responsible for producing what is displayed. While certainly not the only generative process responsible for a power law, the preferential attachment model, first outlined in the physics literature by Barabási & Albert, is among the likely candidates.

Confronting much of the extant literature, query as to whether a closed form equilibria based analytical apparatus (punctuated or otherwise) is up to the task of describing the relevant dynamics? If anything, the distributions displayed above provide first-order evidence of a system which is likely to feature dynamics of a non-linear flavor. Indeed, while significant work still remains, the weight of available evidence indicates Law is a Complex Adaptive System. As such, we believe it would be appropriate to leverage the methods typically reserved for the study of complexity. For purposes of generating positive legal theory, we believe agent based models, dynamic network analysis and other methods of computational social science offer great potential. We encourage scholars to consider learning more about these approaches.

Law as a Seamless Web? Part III

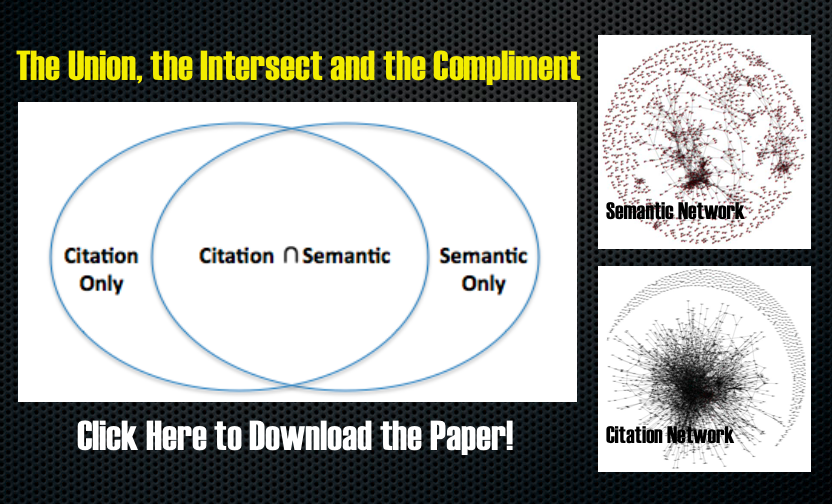

This is the third installment of posts related to our paper Law as a Seamless Web? Comparison of Various Network Representations of the United States Supreme Court Corpus (1791-2005) previous posts can be found (here) and (here). As previewed in the earlier posts, we believe comparing the Union, the Intersect and the Compliment of the SCOTUS semantic and citation networks is at the heart of an empirical evaluation of Law as a Seamless Web …. from the paper….

“Though law is almost certainly a web, questions regarding its interconnectedness remain. Building upon themes of Maitland, Professor Solum has properly raised questions as to whether or not the web of law is “seamless”. By leveraging the tools of computer science and applied graph theory, we believe that an empirical evaluation of this question is at last possible. In that vein, consider Figure 9, which offers several possible topological locations that might be populated by components of the graphs discussed herein. We believe future research should consider the relevant information contained in the union, intersection, and complement of our citation and semantic networks.

While we leave a detailed substantive interpretation for subsequent work, it is worth broadly considering the information defined in Figure 9. For example, the intersect (∩) displayed in Figure 9 defines the set of cases that feature both semantic similarity and a direct citation linkage. In general, these are likely communities of well-defined topical domains. Of greater interest to an empirical evaluation of the law as a seamless web, is likely the magnitude and composition of the Citation Only and Semantic Only subsets. Subject to future empirical investigation, we believe the Citation Only components of the graph may represent the exact type of concept exportation to and from particular semantic domains that would indeed make the law a seamless web.”

Law as a Seamless Web? Part II

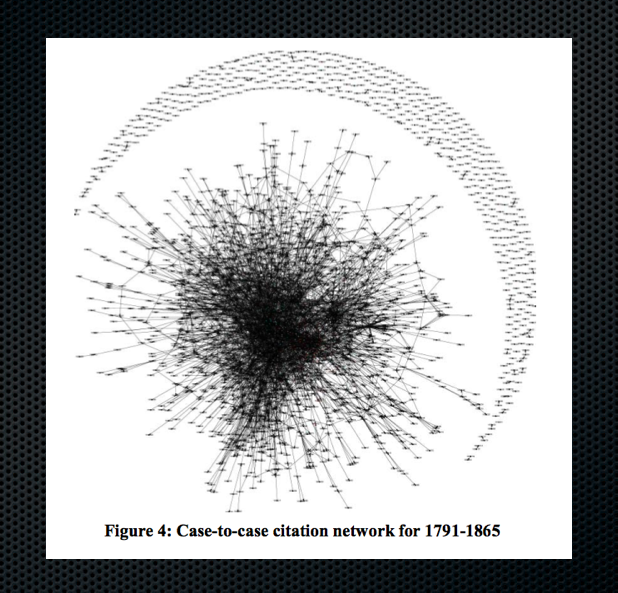

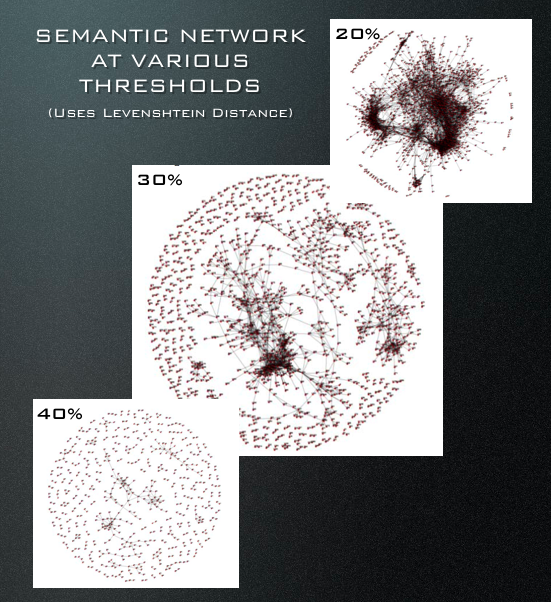

In our paper Law as a Seamless Web, we offer a first-order method to generate case-to-case and opinionunit-to-opinionunit semantic networks. As constructed in the figure above, nodes represent cases decided between 1791-1865 while edges are drawn when two cases possess a certain threshold of semantic similarity. Except for the definition of edges, the process of constructing the semantic graph is identical to that of the citation graph we offered in the prior post. While computer science/computational linguistics offers a variety of possible semantic similarity measures, we choose to employ a commonly used measure. Here a description from the paper:

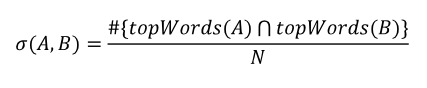

“Semantic similarity measures are the focus of significant work in computational linguistics. Given the scope of the dataset, we have chosen a first-order method for calculating similarity. After lemmatizing the text of the case with WordNet, we store the nouns with the top N frequencies for each case or opinion unit. We define the similarity between two cases or opinion units A and B as the percentage of words that are shared between the top words of A and top words of B.

An edge exists between A and B in the set of edges if σ (A,B) exceeds some threshold. This threshold is the minimum similarity necessary for the graph to represent the presence of a semantic connection.”

An edge exists between A and B in the set of edges if σ (A,B) exceeds some threshold. This threshold is the minimum similarity necessary for the graph to represent the presence of a semantic connection.”

As this a technical paper, it is slanted toward demonstrating proof of methodological concept rather than covering significant substantive ground. With that said, we do offer a hint of our broader substantive goal of detecting the spread of legal concepts between various topical domains. Specifically, with respect to enriching positive political theory, we believe union, intersect and compliment of the semantic and citation networks are really important. More on this point is forthcoming in a subsequent post…

Reading List — Law as a Complex System [Repost from May 15th]

Several months ago, I put together this syllabus for use in a future seminar course Law as a Complex System. This contains far more content than would be practical for the typical 2 credit seminar. However, I have decided to repost this because it could also serve as a reading list for anyone who is interested in learning more about the methodological tradition from which must of our scholarship is drawn. If you see any law related scholarship you believe should be included please feel free to email me.

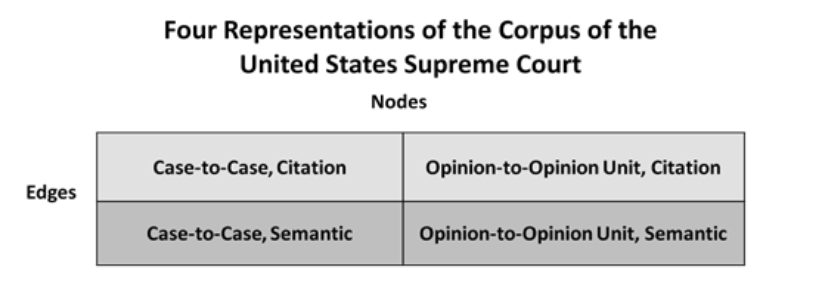

Law as a Seamless Web?

We have recently posted Law as a Seamless Web? Comparison of Various Network Representations of the United States Supreme Court Corpus (1791-2005) to the SSRN. Given this is the first of several posts about the paper, I will speak broadly and leave details for a subsequent post. From the abstract “As research of judicial citation and semantic networks transitions from a strict focus on the structural characteristics of these networks to the evolutionary dynamics behind their growth, it becomes even more important to develop theoretically coherent and empirically grounded ideas about the nature of edges and nodes. In this paper, we move in this direction on several fronts …. Specifically, nodes represent whole cases or individual ‘opinion units’ within cases. Edges represent either citations or semantic connections.” The table below outlines several possible network representations for the USSC corpus.

The goal of the paper is to do some technical and conceptual work. It is a small slice of broader project with James Fowler (UCSD) and James Spriggs (WashU). We recently presented findings from the primary project at the Networks in Political Science Conference. The main project is entitled The Development of Community Structure in the Supreme Court’s Network of Citations and we hope to have a version of this paper on the SSRN soon. In the meantime, we plan additional discussion of Law as a Seamless Web in the days to come.