Tag: supreme court

Law as a Seamless Web? Part III

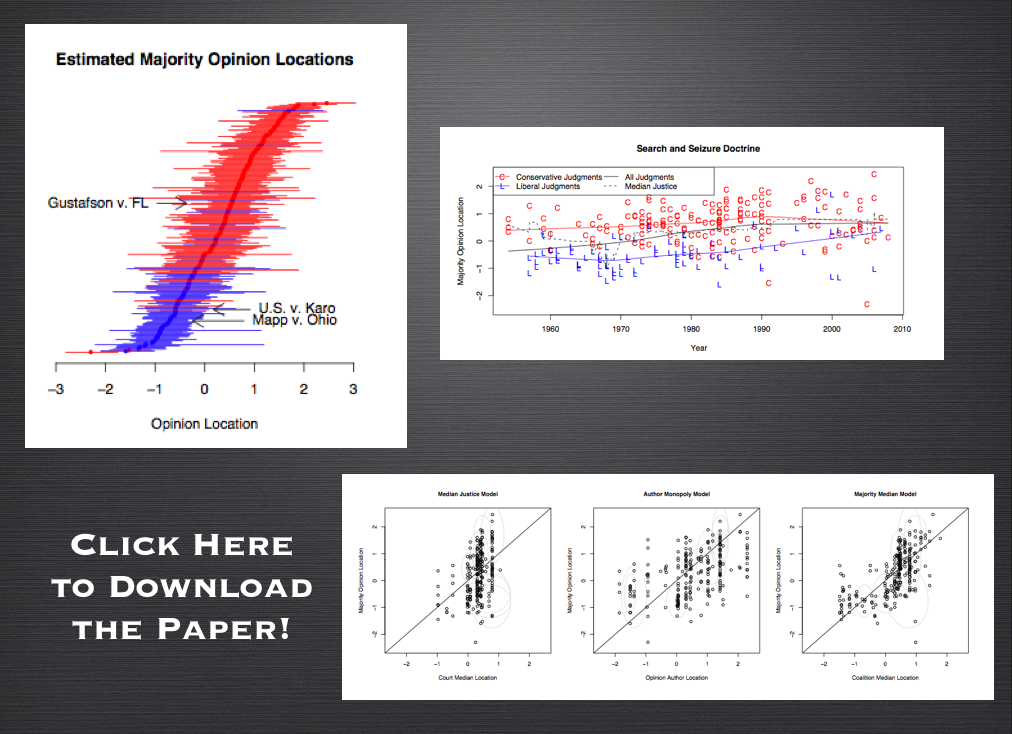

This is the third installment of posts related to our paper Law as a Seamless Web? Comparison of Various Network Representations of the United States Supreme Court Corpus (1791-2005) previous posts can be found (here) and (here). As previewed in the earlier posts, we believe comparing the Union, the Intersect and the Compliment of the SCOTUS semantic and citation networks is at the heart of an empirical evaluation of Law as a Seamless Web …. from the paper….

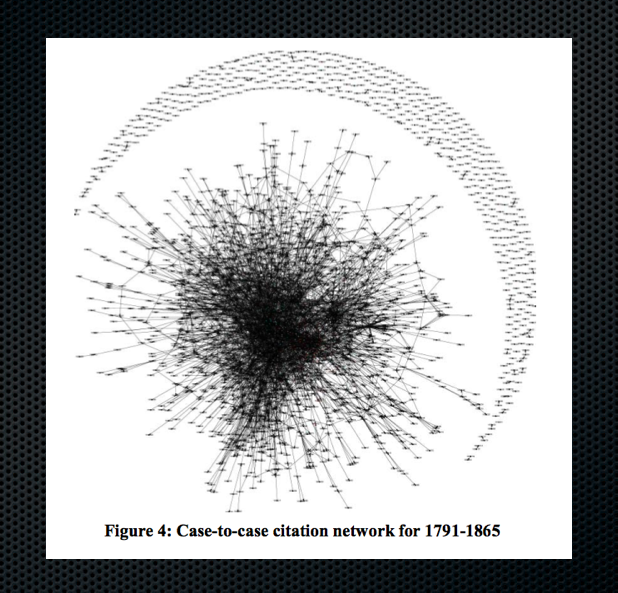

“Though law is almost certainly a web, questions regarding its interconnectedness remain. Building upon themes of Maitland, Professor Solum has properly raised questions as to whether or not the web of law is “seamless”. By leveraging the tools of computer science and applied graph theory, we believe that an empirical evaluation of this question is at last possible. In that vein, consider Figure 9, which offers several possible topological locations that might be populated by components of the graphs discussed herein. We believe future research should consider the relevant information contained in the union, intersection, and complement of our citation and semantic networks.

While we leave a detailed substantive interpretation for subsequent work, it is worth broadly considering the information defined in Figure 9. For example, the intersect (∩) displayed in Figure 9 defines the set of cases that feature both semantic similarity and a direct citation linkage. In general, these are likely communities of well-defined topical domains. Of greater interest to an empirical evaluation of the law as a seamless web, is likely the magnitude and composition of the Citation Only and Semantic Only subsets. Subject to future empirical investigation, we believe the Citation Only components of the graph may represent the exact type of concept exportation to and from particular semantic domains that would indeed make the law a seamless web.”

Institutional Rules, Strategic Behavior, Agenda Control & Inferences — Explaining Chief Justice Roberts Anomalous Decision in NAMUNDO

Agenda Control and Careful Inferences

What are the class of potential inferences one should draw when the Chief Justice behaves in a manner which would appear at odds with our prior understandings of his jurisprudence? As I have argued in my previous article Institutional Rules, Strategic Behavior and the Legacy of Chief Justice William Rehnquist: Setting the Record Straight on Dickerson v. United States, there is significant reason to be careful about the class of inferences one draws under conditions similar to those accompanying yesterday’s decision in NAMUNDO v. Holder.

A significant strain of the literature in political science is devoted to studying the power of agenda control. The primary power of Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court is the power of opinion assignment. This includes the right of the Chief to assign to himself the task of opinion writing. Of course, this authority is qualifed as it only applies when he finds himself in the majority coalition. If he finds himself outside of the majority, the Senior Associate Justice in the majority is permitted to exercise this important authority.

The opinion assignment norm provides a significant incentive for the Chief Justice to behave “strategically.” Specifically, in instances where the majority of the court is unwilling to support his preferred outcome, the Chief still has an incentive to join the majority in order to do “damage control.” For example, he can attempt to author a watered-down opinion or an opinion which leaves the major substantive issues for another day.

The Ghost of Dickerson v. United States

Consider as an illustrative example, Justice Rehnquist’s behavior in the 2000 case, Dickerson v. United States. In Dickerson, the Supreme Court was called to consider the ultimate constitutionality of its landmark decision in Miranda v. Arizona. Prior to the Court’s decision, even Miranda’s strongest supporters had expressed significant concern regarding its continued viability. As I sat in the audience on the day of the Dickerson decision, this concern was only heightened when Justice Rehnquist indicated he would deliver the court’s majority opinion.

Chief Justice Rehnquist prior Miranda related jurisprudence indicated a significant hostility to the Court landmark 1966 ruling. In fact, in every decision prior to Miranda he either voted to limit or undercut the Court’s Miranda doctrine. In 57 out of 57 prior cases, the Miranda doctrine had no friend in William Rehnquist. Between his decision in Dickerson and his death, the Rehnquist-led Court considered 5 major Miranda-related cases. In each of these cases, the Chief resumed exactly where he left off prior to Dickerson. He consistently voted to undercut the holding and virtually ignored his own Dickerson opinion.

Chief Justice Rehnquist’s former law clerk, Ted Cruz, writing about the Dickerson decision in a eulogy in the Harvard Law Review, essentially acknowledged the strategic nature of the decision “it was the best that could be gotten from the current members of the Court.” From a doctrinal perspective, his decision was fairly opaque. For example, in responding to questions regarding Dickerson’s logical underpinning Ted Cruz stated, “do not ask why, and please, never, ever, ever cite this opinion for any reason.”

The Strategic Decision in NAMUNDO v. Holder?

Nearly four years after the death of Chief Justice Rehnquist, another socially important decision would be surprisingly authored by a Chief Justice who initially appeared hostile to the question at issue. This time it was Chief Justice John Roberts, a jurist initially socialized in the ways of the high court in the early 1980’s chambers of then Justice William Rehnquist.

In yesterday’s decision in NAMUNDO v. Holder, Chief Justice Roberts authored an 8-1 decision. Leading election law scholars including Professor Rick Hasen have initially described it as “an interpretation of the Act virtually no lawyer thought was plausible.” The lesson from Dickerson and other such cases is strategic behavior on the part of the Chief is always possible. Once it is apparent he does not have the requisite votes to reach his desired policy outcome–what is a strategic Chief Justice to do? Do damage control, limit the core holding or as Professor Gerken has characterized yesterday’s ruling, “punt.”

Law as a Seamless Web?

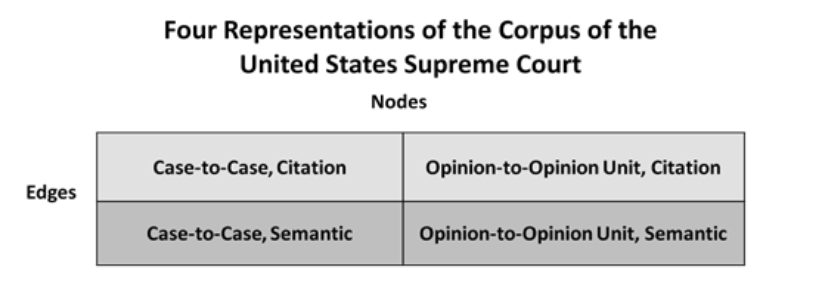

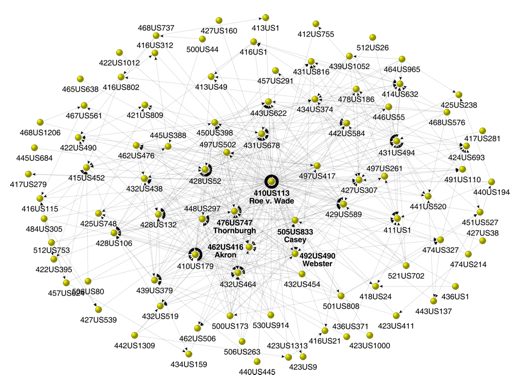

We have recently posted Law as a Seamless Web? Comparison of Various Network Representations of the United States Supreme Court Corpus (1791-2005) to the SSRN. Given this is the first of several posts about the paper, I will speak broadly and leave details for a subsequent post. From the abstract “As research of judicial citation and semantic networks transitions from a strict focus on the structural characteristics of these networks to the evolutionary dynamics behind their growth, it becomes even more important to develop theoretically coherent and empirically grounded ideas about the nature of edges and nodes. In this paper, we move in this direction on several fronts …. Specifically, nodes represent whole cases or individual ‘opinion units’ within cases. Edges represent either citations or semantic connections.” The table below outlines several possible network representations for the USSC corpus.

The goal of the paper is to do some technical and conceptual work. It is a small slice of broader project with James Fowler (UCSD) and James Spriggs (WashU). We recently presented findings from the primary project at the Networks in Political Science Conference. The main project is entitled The Development of Community Structure in the Supreme Court’s Network of Citations and we hope to have a version of this paper on the SSRN soon. In the meantime, we plan additional discussion of Law as a Seamless Web in the days to come.

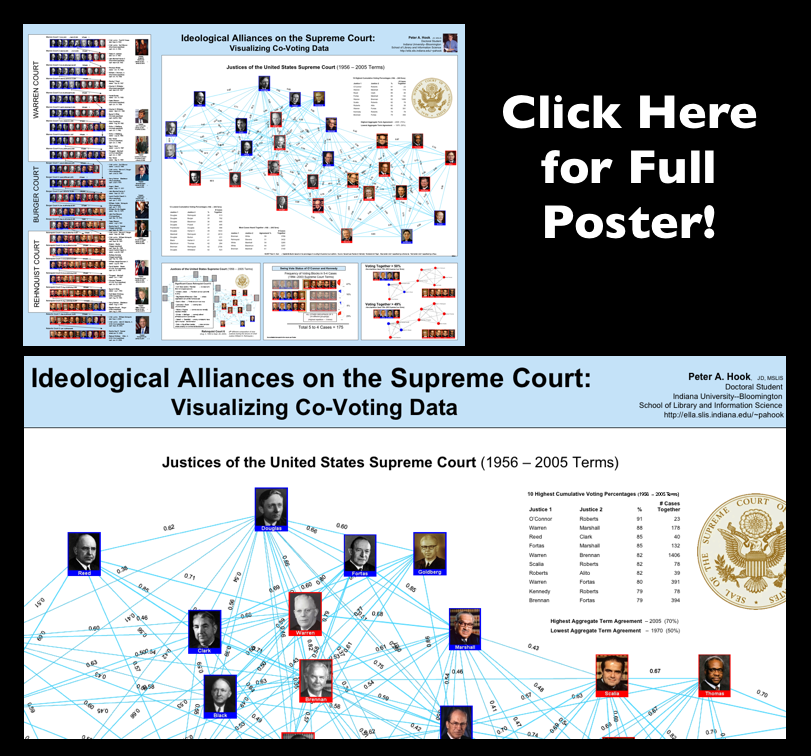

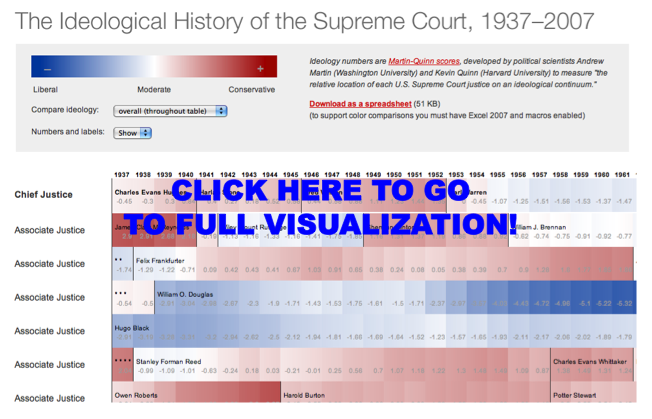

Visualization of the Ideological History of the Supreme Court

Here is a cool visual for the Martin-Quinn Scores. For those of you not familiar, the Martin-Quinn paper and “MQ Scores” represented a significant breakthrough in the field of judicial politics. On that note, Stephen Jessee & Alexander Tahk have done a nice job both bringing their data up to date and extending their work. For those interested, click on the visual above and check out all of the relevant links contained within this post.

An Exchange in Need of Empirics and an Analytical or Computational Model

On a recent flight, I read Jeffrey Toobin’s New Yorker Article on Chief Justice Roberts entitled “No More Mr. Nice Guy”. The exchange quoted above is drawn from this article. While I believe it is appropriate to engage empirical data where available, the underlying discussion is not one exclusively subjectable to empirical inquiry. Rather, it is, at least in part, a question in need of a formal theoretic model. Justice Roberts and Mr. Katyal are implicitly discussing a “state of the world” not yet realized but which would be realized if the statute were not to exist. What would benefit the discussion is principled manner to adjudicate between these two inferences drawn above. Namely, it would be useful to fully evaluate what behavior would likely follow if the statute were not to exist.

There exist a variety of mathematical modeling techniques which could inject some much needed rigor into the above discussion. To my knowledge, such an applied model has yet to be offered. The Supreme Court’s decision in the matter is soon forthcoming. Given the nature of the exchange above, there is reason to believe that if Chief Justice Roberts prevails ….we will get our model as the “state of the world” discussed above will no longer be hypothetical….

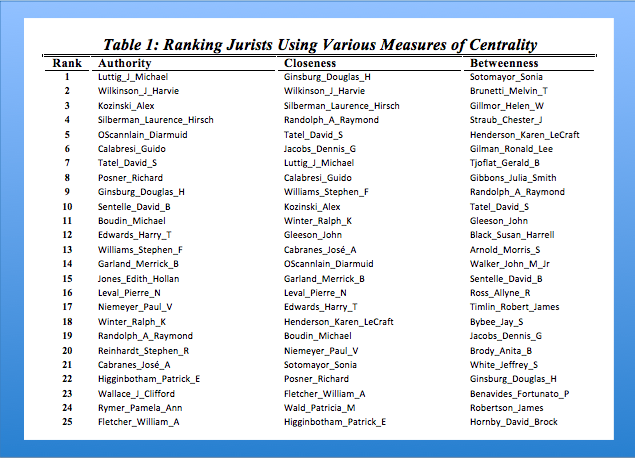

Measuring the Centrality of Federal Judges

Above are some graph statistics from our paper Hustle and Flow: A Social Network Analysis of the American Federal Judiciary. The paper measures the aggregated window of 1995-2005. These, of course, are not the only measures of centrality but they are commonly used in the network science literature. If you are interested — click through to the paper for a description of how these measures are calculated.

We believe these and other elements of the paper offer a good cut on the question of social prestige within the American Federal Judiciary. For example, in the paper we offer a graph visualization where Judge now Justice Alito as well as Judge turned Attorney General Michael Mukasey occupy an extremely central social position (just outside of the Top 25). We think this is useful because their social prestige is measured at a time period prior to their respective nominations. With appropriate control variables for the respective office in question … perhaps we might have been able to predict their nomination?

For purposes of the current Supreme Court opening and conditioned on the selection of a lower court justice with “blue team” credentials, we believe these graph statistics indicate Judge Sonia Sotomayor, Judge Merrick Garland , Judge William Fletcher & Judge David Tatel all occupy high levels of social prestige among their fellow judges and justices. Debate regarding qualifications of various individuals is likely to continue. While certainly not dispositive, we thought it appropriate to offer some social scientific evidence on the question.

President Obama might go outside the tradtional Federal Court of Appeals judge on this round. For example, Governor Jennifer Granholm, Solicitor General Elena Kagan and Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano appear to be on the short list. However, keep these names in mind as this is probably not President Obama’s last nomination to the high court.

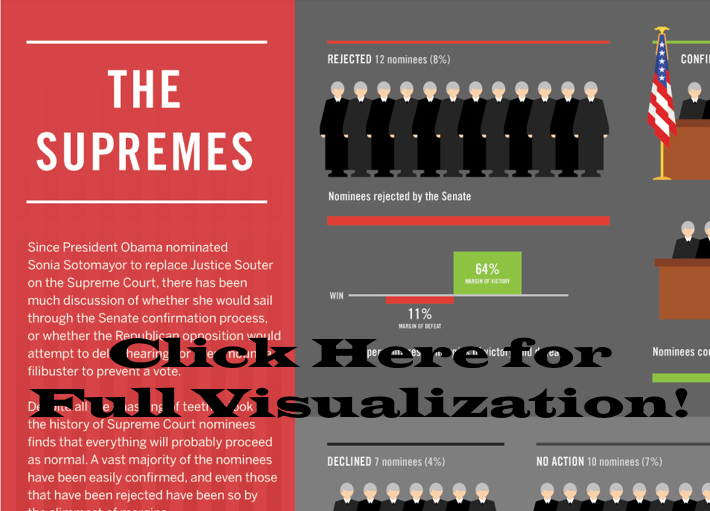

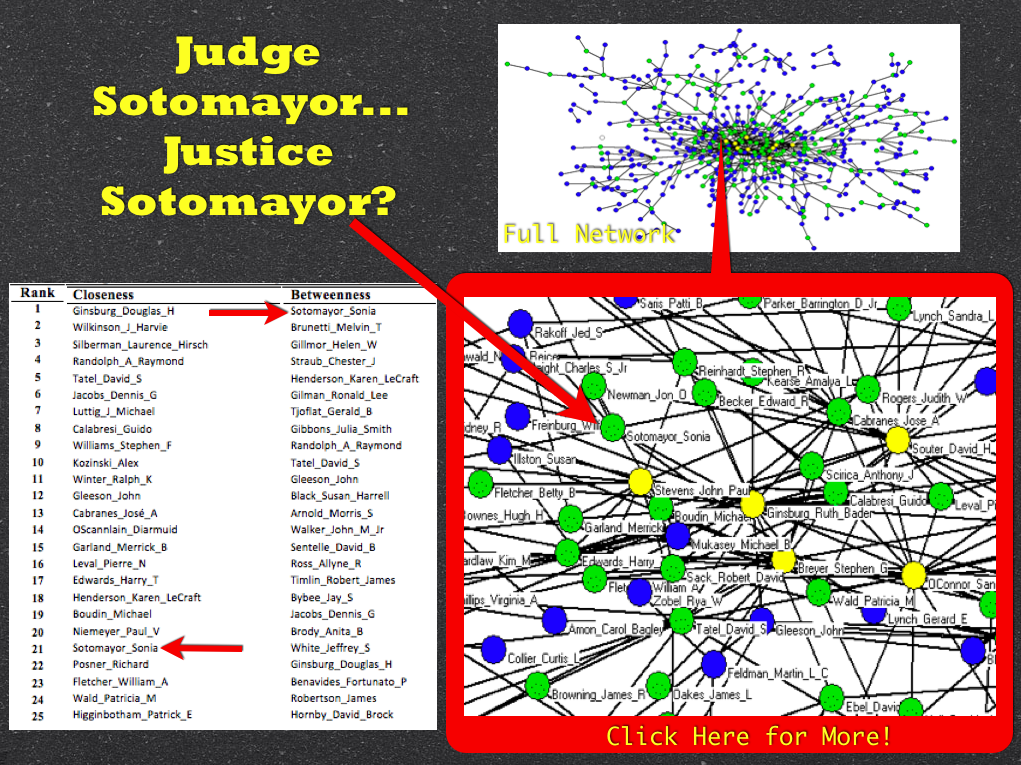

Judge Sonia Sotomayor ⇒ Justice Sotomayor?

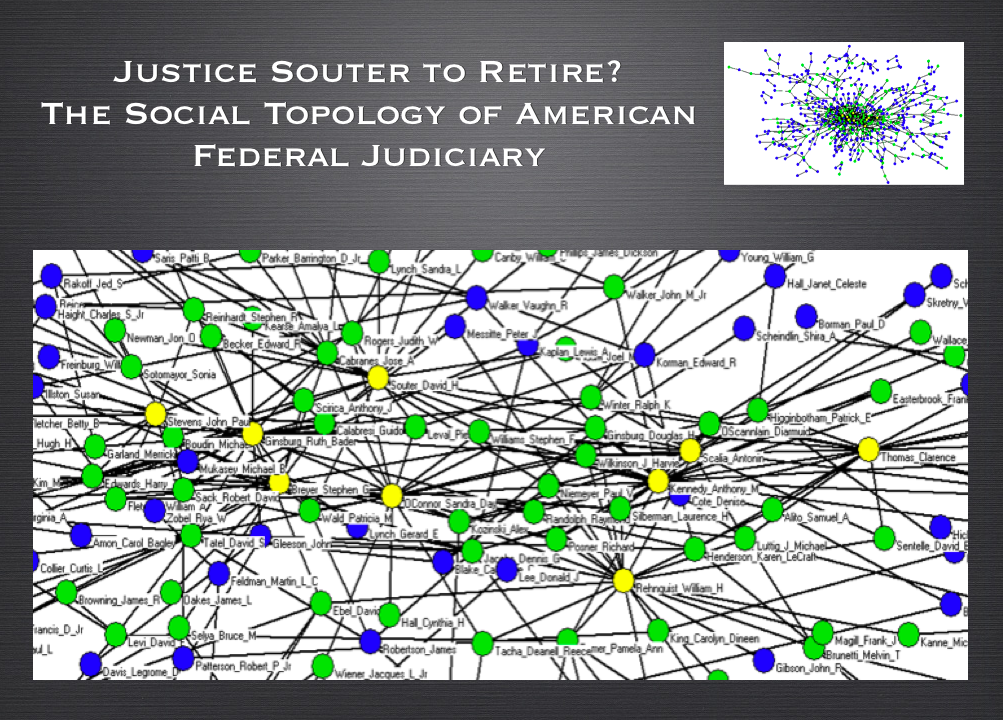

Justice Souter’s recently announced retirement has generated significant speculation regarding the potential nominee President Obama might select.

Barring some unknown skeleton in her closet, if President Obama seeks to (1) select a Federal Court of Appeals Judge and (2) increase the diversity of the Court on multiple dimensions …. well … Judge Sotomayor would have to be the frontrunner.

The picture and graph statistics pictured above are drawn from our paper Hustle and Flow: A Social Network Analysis of the American Federal Judiciary. In the paper, we offer a mapping of the social topology of the American Federal Judiciary. Built upon data aggregated over the Natural Rehnquist Court (1995-2004), we find Judge Sotomayor holds a position of significant social prominence.

To read more on operationalization, etc.—click on the slide above or click here.

A number of commentators have suggested President Obama might forgo nominating a sitting judge — instead choosing an academic or politician. This is certainly a possibility and in that vein let me reveal my bias in favor of Gov. Jennifer Granholm (for whom I formerly worked).

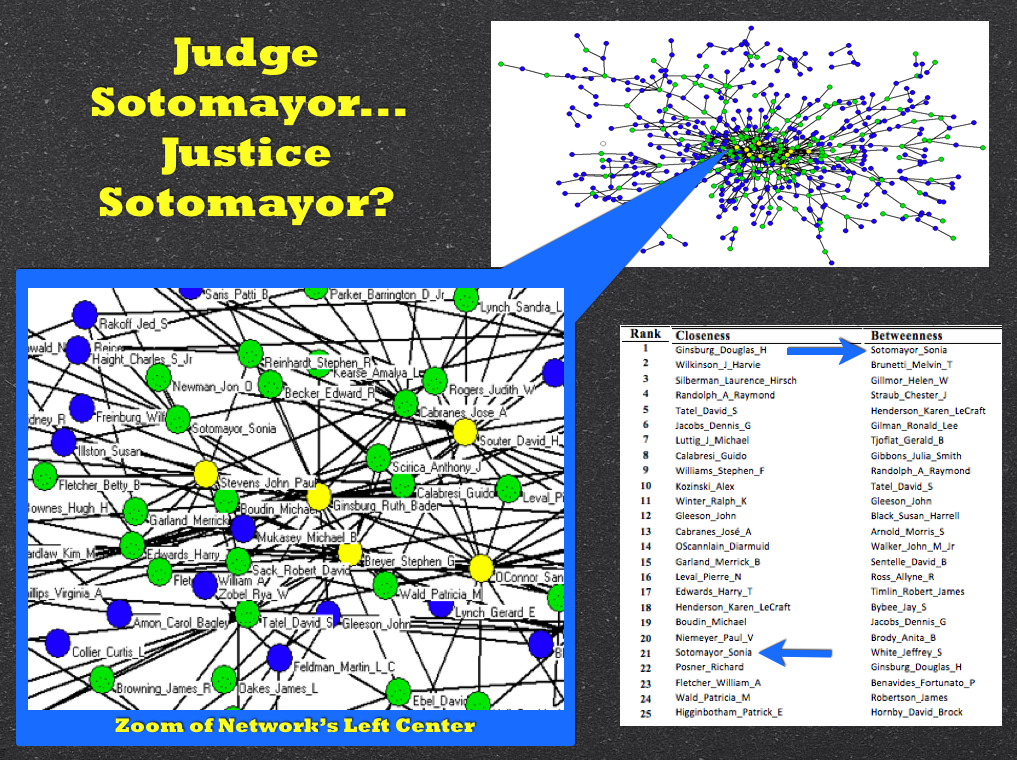

Justice Souter to Retire….Possible Replacements?…Here is a Mapping of Socially Prominent Jurists in the American Federal Judiciary

NPR’s Nina Totenberg is reporting that Justice Souter is planning to retire at the end of the current Supreme Court Term. As noted in the NPR report, the short list of replacements may include Elena Kagan, Diane Wood and/or Sonia Sotomayor (who is in the network above near Justice Stevens). If President Obama decides to look beyond this early short list, he might consider one of the socially prominent federal jurist mapped in above visualization. We have a much more detailed prior post on the underlying paper Hustle and Flow: A Social Network Analysis of the American Federal Judiciary located here. To see the full visualization contained within the paper, click on the slide above or click here.

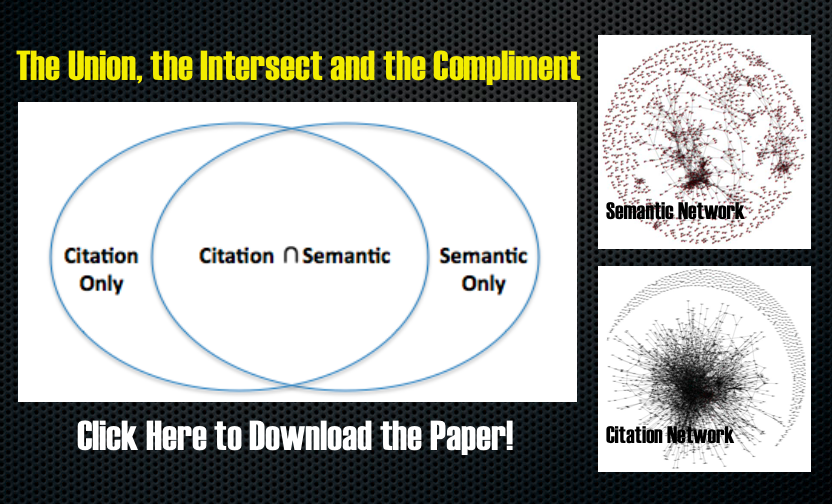

Taking Judicial Content Seriously–Lupu & Fowler’s Strategic Content Model

In my conversations with judicial politics scholars, many lament how many of our existing approaches tend to ignore opinion content. For those interested in embedding opinion content into existing theories of judicial decision making … consider Yonatan Lupu & James Fowler’s paper recently posted to the SSRN.

The authors present a strategic model of judicial bargaining over opinion content. They note … “we find that the Court generates opinions that are better grounded in law when more justices write concurring opinions.” To generate the specification for “grounding in law” the authors use Kleinberg’s Hubs and Authorities Algorithm calculated at the time the opinion was authored. The Strategic Content Paper is available here.

The visual above is drawn from a related Fowler project located here. Another very worthwhile paper authored by Fowler, Johnson, Spriggs, Jeon & Wahlbeck is located here.

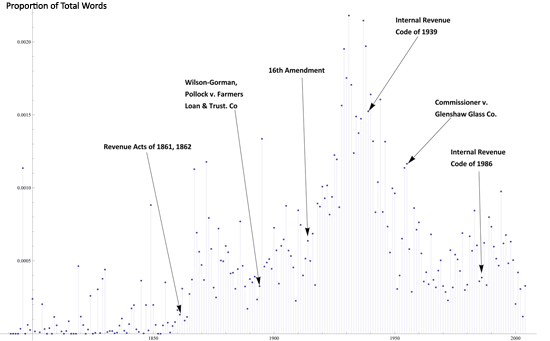

Tax Day! A First-Order History of the Supreme Court and Tax

Click to view the full image.

In honor of Tax Day, we’ve produced a simple time series representation of the Supreme Court and tax. The above plot shows the how often the word “tax” occurs in the cases of the Supreme Court, for each year – that is, what proportion of all words in every case in a given year are the word “tax.” The data underneath includes non-procedural cases from 1790 to 2004. The arrows highlight important legislation and cases for income tax as well.

Make sure to click through the image to view the full size.

Happy Tax Day!

When is the first term enough?: On approximation in social science

Research in the academic world suffers from the “hammer problem” – that is, the methods we use are often those that we have in our toolbox, not necessarily those that we should be using. This is especially true in computational social science, where we often attempt to directly import well-developed methods from the hard sciences.

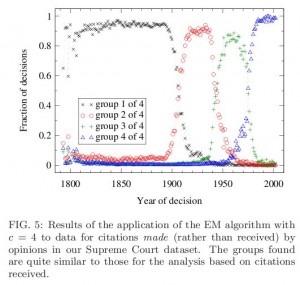

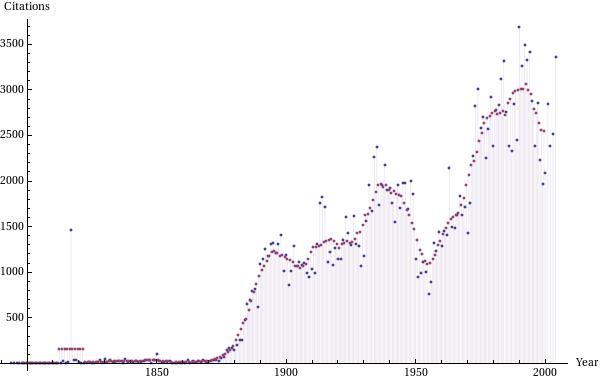

To prove the point, I’d like to highlight one example we’ve come across in our research. In Leicht et al’s Large-scale structure of time evolving citation networks, the authors apply two methods to a simplified representation of the United States Supreme Court citation network. Both of these methods rely on complicated statistical algorithms and require iterative non-linear system solvers. However, the results are consistent, and they detect “events” around 1900, 1940, and 1970.

One first-order alternative to detecting significant “events” in the Court would be to count citations. One might suspect, for instance, that the formation or destruction of law might go hand-in-hand with an acceleration or deceleration in the rate of citation. Such a method is purely conjectural, but costs much less to implement than the methods discussed above.

This figure shows the number of outgoing citations per year in blue, as well as the ten-year moving average in purple. The plot shows jumps that coincide very well with the plot from Leicht, et. al. Thus, although only a first-order approximation to the underlying dynamics, this method would lead historians down a similar path with much less effort.

This example, though simple, is one that really hits home for me. After a week of struggling to align interpretations and methods, this plot convinced me more than any eigenvector or Lagrangian system. Perhaps more importantly, unlike the above methods, you can explain this plot to a lay audience in a fifteen minute talk.