From SSRN abstract: “On August 5, 2014, the Federal Reserve Board and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation criticized shortcomings in the Resolution Plans of the first Systematically Important Financial Institution (SIFI) filers. In his public statement, FDIC Vice Chairman Thomas M. Hoenig said “each plan [submitted by the first 11 filers] is deficient and fails to convincingly demonstrate how, in failure, any one of these firms could overcome obstacles to entering bankruptcy without precipitating a financial crisis.”

From SSRN abstract: “On August 5, 2014, the Federal Reserve Board and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation criticized shortcomings in the Resolution Plans of the first Systematically Important Financial Institution (SIFI) filers. In his public statement, FDIC Vice Chairman Thomas M. Hoenig said “each plan [submitted by the first 11 filers] is deficient and fails to convincingly demonstrate how, in failure, any one of these firms could overcome obstacles to entering bankruptcy without precipitating a financial crisis.”

The first eleven SIFIs — Bank of America, Bank of New York Mellon, Barclays, Citigroup, Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, State Street Corp. and UBS — include some of the largest organizations in the world, with sophisticated internal and external teams of professional advisors. According to Jamie Dimon of JPMorgan Chase in 2013, it took 500 professionals over 1 million hours per year to produce JPMorgan Chase’s annual Resolution plan. With regulatory pressure increasing, that number is likely to be consistent or increasing across first-wave filers, and suggests significant spending by all filers.

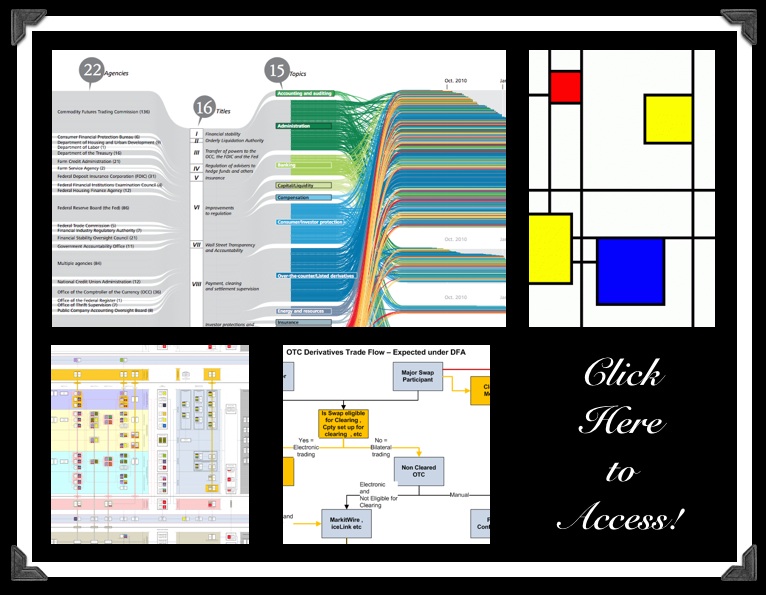

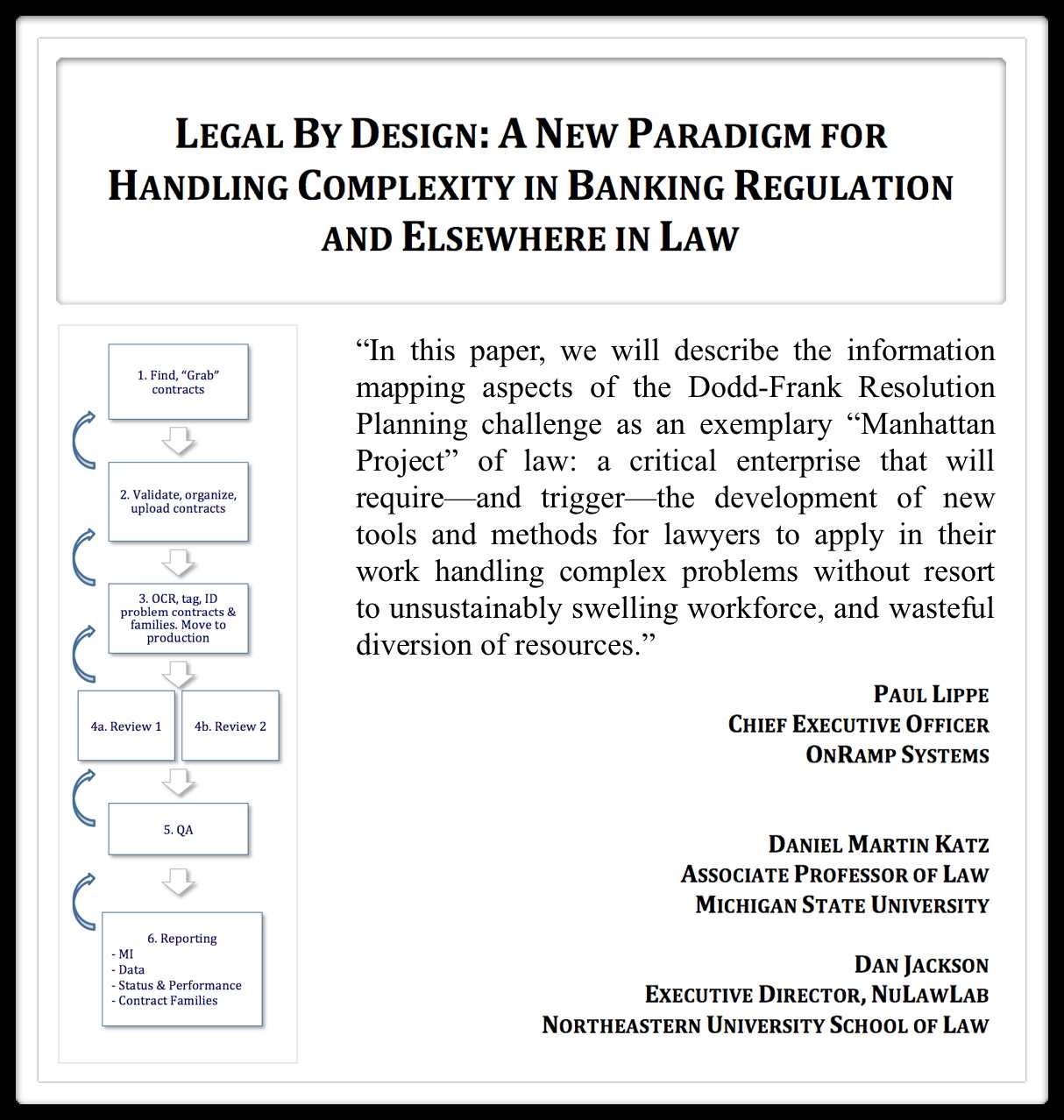

So why were the plans criticized despite heavy compliance investment? The Fed and FDIC identified two common shortcomings across the first 11 SIFI filers: “(i) assumptions that the agencies regard as unrealistic or inadequately supported, such as assumptions about the likely behavior of customers, counterparties, investors, central clearing facilities, and regulators, and (ii) the failure to make, or even to identify, the kinds of changes in firm structure and practices that would be necessary to enhance the prospects for orderly resolution.” We believe this regulatory response highlights, in part, the need for lawyers (and other advisors) to develop approaches that can better manage complexity, encompassing modern notions of design, use of technology, and management of complex systems.

In this paper, we will describe the information mapping aspects of the Resolution Planning challenge as an exemplary “Manhattan Project” of law: a critical enterprise that will require — and trigger — the development of new tools and methods for lawyers to apply in their work handling complex problems without resort to unsustainably swelling workforce, and wasteful diversion of resources. Fortunately, much of this approach has already been developed in innovative Silicon Valley legal departments and has been applied by leading banks. Although much of the focus of the Dodd-Frank Act is on re-organizing and simplifying banks, we will focus here on the information architecture issues which underlie much of what should — and will — change about how law is delivered, not just for Resolution Planning, but more broadly.”