Click on the above picture and you will be taken to the Interactive Gallery of Computational Legal Studies. Once inside the gallery, click on any thumbnail to see the full size image. Each image features a link to supporting materials such as documentation and/or the underlying academic paper. We hope to add more content to gallery over the coming weeks and months — so please check back! Please note that load time may vary depending upon your connection, machine, etc.

Tag: computational legal studies

NetSci 2010 — MIT Media Lab

Tomorrow is the first day of presentations at NetSci2010. Our paper will presented in AM Network Measures Panel. Anyway, for those interested in leveraging network science to study the dynamics of large social and physical systems — the conference promises a fantastic lineup of speakers. Check out the program!

Computational Legal Studies Presentation Slides from the Law.gov Meetings

Thanks to Carl Malamud and the good folks at the University of Colorado Law School and University of Texas Law School for allowing us to participate in their respective law.gov meetings. For those interested in governmental transparency, we believe that Carl Malamud’s on-going national conversation is very important. The video above represents a fixed spaced movie combining the majority of the slides we presented at the two meetings. If the video will not load, click here to access the YouTube Version of the Slides. Enjoy!

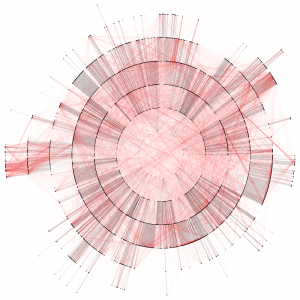

Visualizing Temporal Patterns in the United States Supreme Court’s Network of Citations

The above image is a visualization of temporal citation patterns in the history of the United States Supreme Court. Each case is placed horizontally across the image in chronological order. We then draw citations between cases as curved arcs. We use three distinct arc colors to show qualitative differences between these citations:

- RED arcs correspond to citations within a natural court (e.g., the Rehnquist court citing the Rehnquist court).

- GREEN arcs correspond to citations from one natural court to the previous natural court (e.g., the Rehnquist court citing the Burger court).

- BLUE arcs correspond to citations from one natural court to a natural court prior to the previous natural court (e.g., the the Rehnquist court citing the Marshall court).

- Note that yellow is produced when red and green overlap.

Though there are many ways to interpret this data, we wanted to provide three simple conclusions to draw:

- The number of cases decided within each natural court varies dramatically. For instance, the Rehnquist court decided fewer cases than the Fuller court.

- Most citations are to recent cases, not cases in the distant past.

- The Burger and Rehnquist courts rely heavily on cases from the Hughes, Stone, and Vinson courts

Law.Gov Meeting @ Texas Law School

Tommorow is the Law.gov meeting at Texas Law School where Mike and I will be presenting in the afternoon session. We are looking forward to the discussion! Thanks to Terry Martin and Carl Malamud for organizing the event. For those interested, click on the image above and you will be directed to the agenda for the meeting.

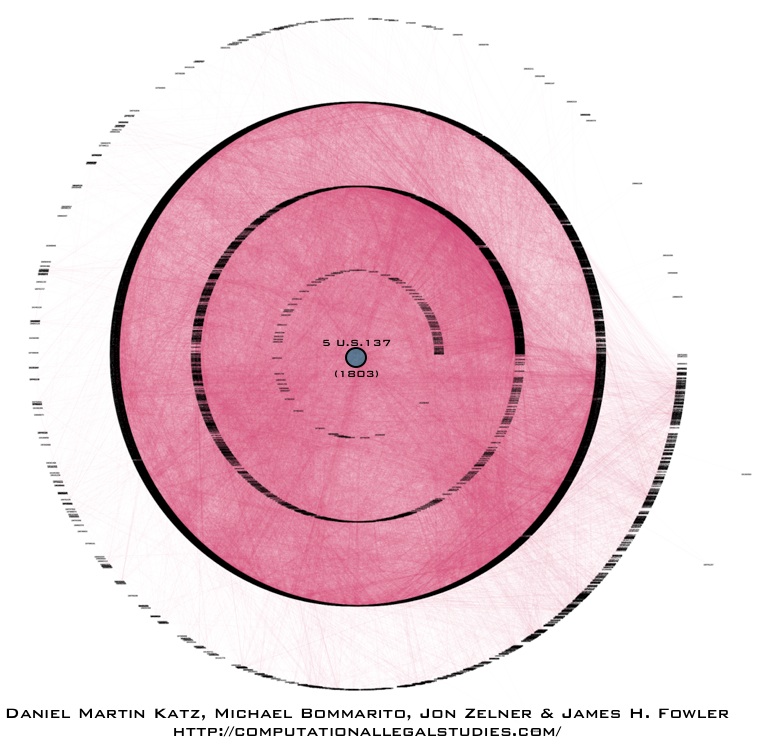

Six Degrees of Marbury v. Madison : A Sink Based Visualization

The visualization above is something we call “six degrees” of Marbury v. Madison. It was originally produced for use in our paper Distance Measures for Dynamic Citation Networks. Due to space considerations, we ended up leaving it on the cutting room floor. However, the visual is designed to highlight the idea of a “sink.”

Sinks are one of the core concepts which we outline in our Distance Measures for Dynamic Citation Networks paper. Looking through the prism of a citation network, sinks are the root to which a given legal concept, academic idea or patent based innovation can be drawn. From each citation in a non-sink node, it is possible to trace the chains of citations back to their root (which we call a sink). In the visualization above, the root or sink node is the famed United States Supreme Court decision Marbury v. Madison. Starting from the center and working out to the edge, the first ring are cases that directly cite Marbury v. Madison. The next ring are cases which cite cases that cite Marbury v. Madison. The next ring are cases which cite cases which cases that cite Marbury v. Madison and so on…

Anyway, one of the major contributions of the Distance Measures for Dynamic Citation Networks paper is that it allows us to use these sinks to create pairwise distance/similarity measure between the ith and jth unit. In this instance, the units in this directed acyclic network are the ith and jth decisions of the United States Supreme Court.

Now, it is important to note cases contain many citations and thus can be oriented relative to many different sinks. So, even if a case can be traced to the Marbury sink – this does not preclude it from being traced to other sinks as well. Also, it is possible to design many mathematical functions to characterize the sink based distance between units. For instance, the importance of a sink might decay as its shortest path length increases. An alternative measure might weight the importance of each sinks by the number of unique ancestors shared between nodes i and j that are descended from a given sink of interest. Indeed, many fine-grained choices are possible but they require justification drawn from the given substantive problem …

Law as a Complex Adaptive System Syllabus -Updated Version 04.24.10

For the past year, Mike and I have been running an undergraduate independent study course entitled Law as a Complex System? Well, it is the end of the academic year here at Michigan and we thought it would be a good idea to sit down and reflect upon the course content. We have made a few important changes to the syllabus and thought we would share the new version with anyone who might be interested. We are really quite happy with where it now stands…

Tax Day: A Mathematical Approach to the Study of the United States Code

April 15th is Tax Day! Unless you’ve filed for an extension or you’re a corporation on your own fiscal year, you’ve hopefully finished your taxes by now!

While you were filing your return, you may have noticed references to the Internal Revenue Code (IRC). The IRC, also known as Title 26, is legal slang for the “Tax Code.” Along with the Treasury Regulations compiled into the Code of Federal Regulations (26 C.F.R.), the Internal Revenue Code contains many of the rules and regulations governing how we can and can’t file our taxes. Even if you prepared your taxes using software like TurboTax, the questions generated by these programs are determined by the rules and regulations within the Tax Code and Treasury Regulations.

Many argue that there are too many of these rules and regulations or that these rules and regulations are too complex. Furthermore, many also claim that the “Tax Code” is becoming larger or more complex over time. Unfortunately, most individuals do not support this claim with solid data. When they do, they often rely on either the number of pages in Title 26 or the CCH Standard Federal Tax Reporter. None of these measures take into consideration the real complexity of the Code, however.

In honor of Tax Day, we’re going to highlight a recent paper that we’ve written that tries to address some of these issues – A Mathematical Approach to the Study of the United States Code. The first point to make is that this paper is a study of the entire United States Code. Title 26, the Tax Code, is actually only one small part of the set of rules and regulations defined in the United States Code. The United States Code as a whole is the largest and arguably most important source of Federal statutory law. Compiled from the legislation and treaties published in the Statutes at Large in 6-year intervals, the entire document contains over 22 million words.

In this paper, we develop a mathematical approach to the study of the large bodies of statutory law and in particular, the United States Code. This approach can be summarized as guided by a representation of the Code as an object with three primary parts:

- A hierarchical network that corresponds to the structure of concept categories.

- A citation network that encodes the interdependence of concepts.

- The language contained within each section.

Given this representation, we then calculate a number of properties for the United States Code in 2008, 2009, and 2010 as provided by the Legal Information Institute at the Cornell University Law School. Our results can be summarized in three points:

- The structure of the United States Code is growing by over 3 sections per day.

- The interdependence of the United States Code is increasing by over 7 citations per day.

- The amount of language in the United States Code is increasing by over 2,000 words per day.

The figure above is an actual image of the structure and interdependence of the United States Code. The black lines correspond to structure and the red lines correspond to interdependence. Though visually stunning, the true implication of this figure is that the United States Code is a very interdependent set of rules and regulations, both within and across concept categories.

If you’re interested in more detail, make sure to read the paper –A Mathematical Approach to the Study of the United States Code. If you’re really interested, make sure to check back in the near future for our forthcoming paper entitled Measuring the Complexity of the United States Code.

The MIT School of Law?

I have to admit that I got totally suckered by this April fools day post over at the Faculty Lounge. I did not carefully read all of the supporting details. So, (a) kudos for them for this great prank and (b) shame on me for skimming!

So I have been mulling it over a little bit … and although it was pitched as a joke … the MIT School of Law sounds like very interesting idea …

I guess part of why I was so willing to believe this post is because, in my estimation, it represented a good assessment of the state of the market for legal education. Namely, MIT School of Law seems like a plausible effort to capture and arguably better serve one particular subset of the market.

We live in the petabyte era and the impacts of the era of ‘big data’ are already remaking many sectors of the economy. It cannot be too long until the scope of available information fundamentally alters the market for legal services. Specifically, in terms of leveraging information technology to improve the quality and efficiency of legal services … my bet is on someone with an interest in attending the MIT Law School.

So, I know what you might be thinking… Isn’t it the case that lots of institutions offer courses and programs that would generally parallel those offered by MIT Law School? Well, yes.

However, I believe that an MIT law school would arguably differ from existing offerings in two important ways:

(1) Given a selective pool of students with prior technical training … the emphasis upon science and technology, etc. could be much more extensive. Indeed, one could imagine a legal curriculum that strongly emphasized science, technology, statistical training, mathematical and computational modeling, etc. There is a growing market for lawyers with this class of skills (but those jobs are currently in non-traditional places).

(2) Like in many other fields, a non-trivial amount of the substantive education is generated through peer-to-peer interaction outside of the classroom. A culture that was exclusively or nearly exclusively devoted to the integration of law, technology, applied math, computer science as well as the social and physical sciences could arguably do a better job of nurturing the development of a particular subset of the broader law student population.

I want to make sure it is clear that this post is not a general affront to state of American legal education. There are some serious issues in American legal education but I will leave this broader reform question to more qualified folks. Instead, this post is related to better serving a narrow slice of the market (i.e. law students with particular class of prior technical training).

Anyway, while this is probably not likely to come to pass … I still thought the idea was worthy of some sort of brief sketch … I mean if one thinks UC-Irvine has stormed the scene … seriously, think about what a MIT law school might be able to do!

Happy Birthday to Computational Legal Studies

On March 17, 2009 we offered our first post here at the Computational Legal Studies Blog. It has been an exciting and fun year. Here are some of the highlights!

The Data Deluge [Via The Economist]

The cover story of this week’s Economist is entitled The Data Deluge. This is, of course, a favorite topic of the hosts of this blog. While a number of folks have already highlighted this trend, we are happy to see a mainstream outlet such the Economist reporting on the era of big data. Indeed, the convergence of rapidly increasing computing power, and decreasing data storage costs, on one side, and large scale data collection and digitization on the other … has already impacted practices in the business, government and scientific communities. There is ample reason to believe that more is on the way.

In our estimation, for the particular class of questions for which data is available, two major implications of the deluge are worth reiterating: (1) no need to make assumptions about the asymptotic performance of a particular sampling frames when population level data is readily available; and (2) what statistical sampling was to the 20th century, data filtering may very well be to the 21st ….

The Development of Structure in the Citation Network of the United States Supreme Court — Now in HD!

What are some of the key takeaway points?

(1) The Supreme Court’s increasing reliance upon its own decisions over the 1800-1830 window.

(2) The important role of maritime/admiralty law in the early years of the Supreme Court’s citation network. At least with respect to the Supreme Court’s citation network, these maritime decisions are the root of the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence.

(3) The increasing centrality of decisions such as Marbury v. Madison, Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee to the overall network.

The Development of Structure in the SCOTUS Citation Network

The visualization offered above is the largest weakly connected component of the citation network of the United States Supreme Court (1800-1829). Each time slice visualizes the aggregate network as of the year in question.

In our paper entitled Distance Measures for Dynamic Citation Networks, we offer some thoughts on the early SCOTUS citation network. In reviewing the visual above note ….“[T]he Court’s early citation practices indicate a general absence of references to its own prior decisions. While the court did invoke well-established legal concepts, those concepts were often originally developed in alternative domains or jurisdictions. At some level, the lack of self-reference and corresponding reliance upon external sources is not terribly surprising. Namely, there often did not exist a set of established Supreme Court precedents for the class of disputes which reached the high court. Thus, it was necessary for the jurisprudence of the United States Supreme Court, seen through the prism of its case-to-case citation network, to transition through a loading phase. During this loading phase, the largest weakly connected component of the graph generally lacked any meaningful clustering. However, this sparsely connected graph would soon give way, and by the early 1820’s, the largest weakly connected component displayed detectable structure.”

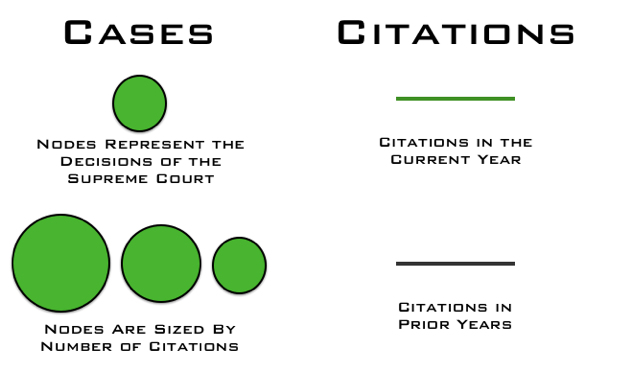

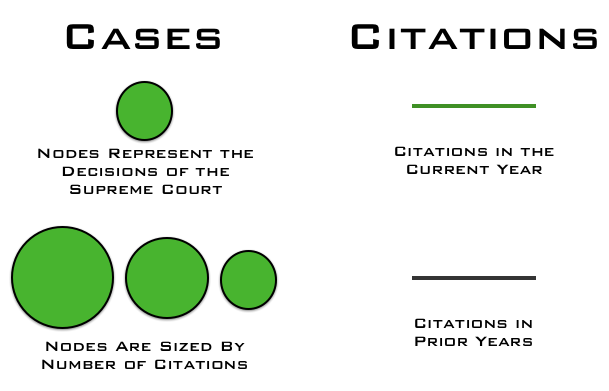

What are the elements of the network?

What are the labels?

To help orient the end-user, the visualization highlights several important decisions of the United States Supreme Court offered within the relevant time period:

Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803) we labeled as ”Marbury”

Murray v. The Charming Betsey, 6 U.S. 64 (1804) we labeled as “Charming Betsey”

Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee, 14 U.S. 304 (1816) we labeled as “Martin’s Lessee”

The Anna Maria, 15 U.S. 327 (1817) we labeled as “Anna Maria”

McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. 316 (1819) we labeled as “McCulloch”

Why do cases not always enter the visualization when they are decided?

As we are interested in the core set of cases, we are only visualizing the largest weakly connected component of the United States Supreme Court citation network. Cases are not added until they are linked to the LWCC. For example, Marbury v. Madison is not added to the visualization until a few years after it is decided.

How do I best view the visualization?

Given this is a high-definition video, it may take few seconds to load. We believe that it is worth the wait. In our view, the video is best consumed (1) Full Screen (2) HD On (3) Scaling Off.

Where can I find related papers?

Here is a non-exhaustive list of related scholarship:

Michael Bommarito, Daniel Katz, Jon Zelner & James Fowler, Distance Measures for Dynamic Citation Networks, Physica A __ (2010 Forthcoming).

Yonatan Lupu & James Fowler, The Strategic Content Model of Supreme Court Opinion Writing, APSA 2009 Toronto Meeting Paper.

Michael Bommarito, Daniel Katz & Jon Zelner, Law as a Seamless Web? Comparison of Various Network Representations of the United States Supreme Court Corpus (1791-2005) in Proceedings of the 12th Intl. Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Law (2009).

Frank Cross, Thomas Smith & Antonio Tomarchio, The Reagan Revolution in the Network of Law, 57 Emory L. J. 1227 (2008).

James Fowler & Sangick Jeon, The Authority of Supreme Court Precedent, 30 Soc. Networks 16 (2008).

Elizabeth Leicht, Gavin Clarkson, Kerby Shedden & Mark Newman, Large-Scale Structure of Time Evolving Citation Networks, 59 European Physics Journal B 75 (2007).

Thomas Smith, The Web of the Law, 44 San Diego L.R. 309 (2007).

James Fowler, Timothy R. Johnson, James F. Spriggs II, Sangick Jeon & Paul J. Wahlbeck, Network Analysis and the Law: Measuring the Legal Importance of Precedents at the U.S. Supreme Court, 15 Political Analysis, 324 (2007).

_

The Development of Structure in the Citation Network of the United States Supreme Court

The Development of Structure in the Citation Network of the United States Supreme Court — Now in HD! from Computational Legal Studies on Vimeo.

What are some of the key takeaway points?

(1) The Supreme Court’s increasing reliance upon its own decisions over the 1800-1830 window.

(2) The important role of maritime/admiralty law in the early years of the Supreme Court’s citation network. At least with respect to the Supreme Court’s citation network, these maritime decisions are the root of the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence.

(3) The increasing centrality of decisions such as Marbury v. Madison, Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee to the overall network.

The Development of Structure in the SCOTUS Citation Network

The visualization offered above is the largest weakly connected component of the citation network of the United States Supreme Court (1800-1829). Each time slice visualizes the aggregate network as of the year in question.

In our paper entitled Distance Measures for Dynamic Citation Networks, we offer some thoughts on the early SCOTUS citation network. In reviewing the visual above note ….“[T]he Court’s early citation practices indicate a general absence of references to its own prior decisions. While the court did invoke well-established legal concepts, those concepts were often originally developed in alternative domains or jurisdictions. At some level, the lack of self-reference and corresponding reliance upon external sources is not terribly surprising. Namely, there often did not exist a set of established Supreme Court precedents for the class of disputes which reached the high court. Thus, it was necessary for the jurisprudence of the United States Supreme Court, seen through the prism of its case-to-case citation network, to transition through a loading phase. During this loading phase, the largest weakly connected component of the graph generally lacked any meaningful clustering. However, this sparsely connected graph would soon give way, and by the early 1820’s, the largest weakly connected component displayed detectable structure.”

What are the elements of the network?

What are the labels?

To help orient the end-user, the visualization highlights several important decisions of the United States Supreme Court offered within the relevant time period:

Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803) we labeled as “Marbury”

Murray v. The Charming Betsey, 6 U.S. 64 (1804) we labeled as “Charming Betsey”

Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee, 14 U.S. 304 (1816) we labeled as “Martin’s Lessee”

The Anna Maria, 15 U.S. 327 (1817) we labeled as “Anna Maria”

McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. 316 (1819) we labeled as “McCulloch”

Why do cases not always enter the visualization when they are decided?

As we are interested in the core set of cases, we are only visualizing the largest weakly connected component of the United States Supreme Court citation network. Cases are not added until they are linked to the LWCC. For example, Marbury v. Madison is not added to the visualization until a few years after it is decided.

How do I best view the visualization?

Those interested in viewing the full screen video—click on the full screen icon contained in the Vimeo bottom banner. Check out the NEW Hi-Def (HD) version of the video!

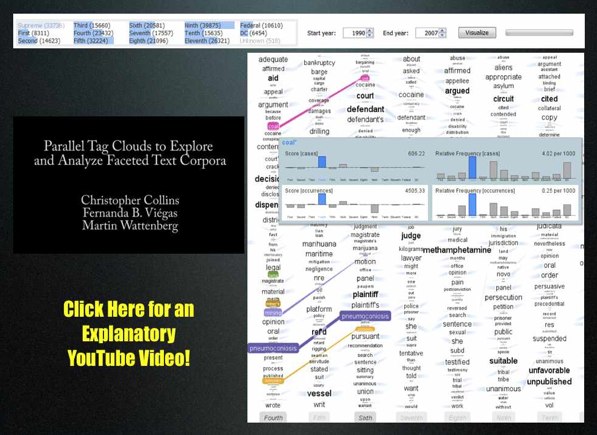

United States Court of Appeals & Parallel Tag Clouds from IBM Research [Repost from 10/23]

Download the paper: Collins, Christopher; Viégas, Fernanda B.; Wattenberg, Martin. Parallel Tag Clouds to Explore Faceted Text Corpora To appear in Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Visual Analytics Science and Technology (VAST), October, 2009. [Note: The Paper is 24.5 MB]

Here is the abstract: Do court cases differ from place to place? What kind of picture do we get by looking at a country’s collection of law cases? We introduce Parallel Tag Clouds: a new way to visualize differences amongst facets of very large metadata-rich text corpora. We have pointed Parallel Tag Clouds at a collection of over 600,000 US Circuit Court decisions spanning a period of 50 years and have discovered regional as well as linguistic differences between courts. The visualization technique combines graphical elements from parallel coordinates and traditional tag clouds to provide rich overviews of a document collection while acting as an entry point for exploration of individual texts. We augment basic parallel tag clouds with a details-in-context display and an option to visualize changes over a second facet of the data, such as time. We also address text mining challenges such as selecting the best words to visualize, and how to do so in reasonable time periods to maintain interactivity.

Science Magazine Policy Forum: Accessible Reproducible Research

From the Abstract … “Scientific publications have at least two goals: (i) to announce a result and (ii) to convince readers that the result is correct. Mathematics papers are expected to contain a proof complete enough to allow knowledgeable readers to fill in any details. Papers in experimental science should describe the results and provide a clear enough protocol to allow successful repetition and extension.” (Institutional or Individual Subscription Required).