–

How Python can Turn the Internet into your Dataset: Part 1

As we covered earlier, Drew Conway over at Zero Intelligence Agents has gotten off to a great start with his first two tutorials on collecting and managing web data with Python. However, critics of such automated collection might argue that the cost of writing and maintaining this code is higher than the return for small datasets. Furthermore, someone still needs to manually enter the players of interest for this code to work.

To convince these remaining skeptics, I decided to put together an example where automated collection is clearly the winner.

Problem: Imagine you wanted to compare Drew’s NY Giants draft picks with the league as a whole. How would you go about obtaining data on the rest of the league’s players?

Human Solution: If you planned to do this the old-fashioned manual way, you would probably decide to collect the player data team-by-team. On the NFL.com website, the first step would thus be to find the list of team rosters:

http://www.nfl.com/players/search?category=team&playerType=current

Now, you’d need to click through to each team’s roster. For instance, if you’re from Ann Arbor, you might be a Lion’s fan…

http://www.nfl.com/players/search?category=team&filter=1540&playerType=current

This is the list of current players for Detroit Lions. In order to collect the desired player info, however, you’d again have follow the link to each player’s profile page. For instance, you might want to check out the Lion’s own first round pick:

http://www.nfl.com/players/matthewstafford/profile?id=STA134157

At last, you can copy down Stafford’s statistics. Simple enough, right? This might take all of 30 seconds with page load times and your spreadsheet entry.

The Lions have more than 70 players rostered (more than just active players); let’s assume this is representative. There are 32 teams in the NFL. By even a conservative estimate, there are over 2000 players you’d need to collect data. If each of the 2000 players took 30 seconds, you’d need about 17 man hours to collect the data. You might hand this data entry over to a team of bored undergrads or graduate students, but then you’d need to worry about double-coding and cost of labor. Furthermore, what if you wanted to extend this analysis to historical players as well? You better start looking for a source of funding…

What if there was an easier way?

Python Solution:

The solution requires just 100 lines of code. An experienced Python programmer can produce this kind of code in half an hour over a beer at a place like Ashley’s. The program itself can download the entire data set in less than half an hour. In total, this data set is the product of less than an hour of total time.

How long would it take your team of undergrads? Think about all the paperwork, explanations, formatting problems, delays, and cost…

The end result is a spreadsheet with the name, weight, age, height in inches, college, and NFL team for 2,520 players. This isn’t even the full list – for the purpose of this tutorial, players with missing data, e.g., unknown height, are not recorded.

You can view the spreadsheet here. In upcoming tutorials, I’ll cover how to visualize and analyze this data in both standard statistical models as well as network models.

In the meantime, think about which of these two solutions makes for a better world.

How to Use Python to Collect Data from the Web [From Drew Conway]

We wanted to highlight a couple of very interesting posts by Drew Conway of Zero Intelligence Agents. While not simple, the programming language python offers significant returns upon investment. From a data acquisition standpoint, python has made what seemed impossible quite possible. As a side note, this code looks like our first Bommarito led Ann Arbor Python Club effort to download and process NBA Box Scores…. you know it is all about trying to win the fantasy league…!

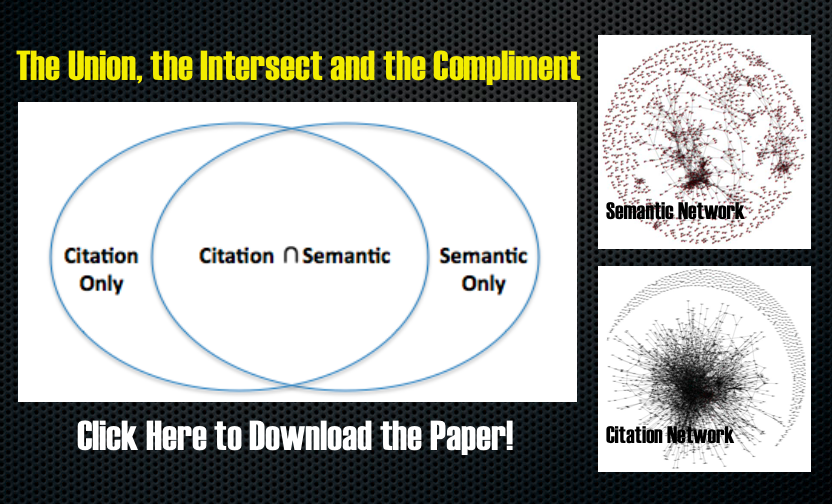

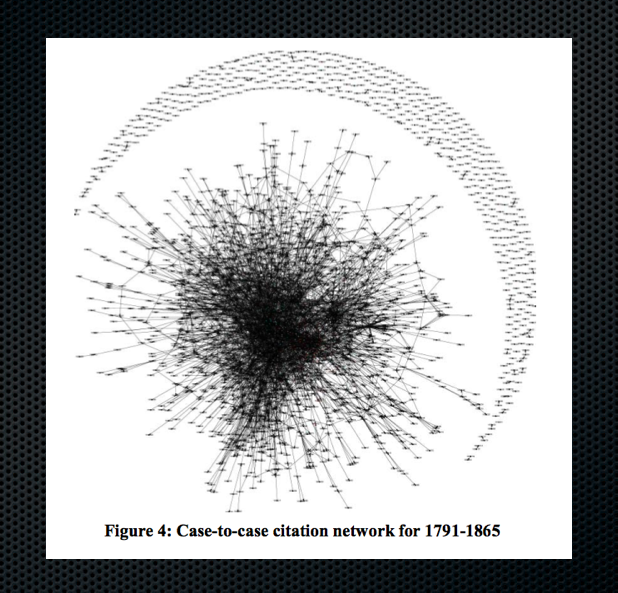

Law as a Seamless Web? Part III

This is the third installment of posts related to our paper Law as a Seamless Web? Comparison of Various Network Representations of the United States Supreme Court Corpus (1791-2005) previous posts can be found (here) and (here). As previewed in the earlier posts, we believe comparing the Union, the Intersect and the Compliment of the SCOTUS semantic and citation networks is at the heart of an empirical evaluation of Law as a Seamless Web …. from the paper….

“Though law is almost certainly a web, questions regarding its interconnectedness remain. Building upon themes of Maitland, Professor Solum has properly raised questions as to whether or not the web of law is “seamless”. By leveraging the tools of computer science and applied graph theory, we believe that an empirical evaluation of this question is at last possible. In that vein, consider Figure 9, which offers several possible topological locations that might be populated by components of the graphs discussed herein. We believe future research should consider the relevant information contained in the union, intersection, and complement of our citation and semantic networks.

While we leave a detailed substantive interpretation for subsequent work, it is worth broadly considering the information defined in Figure 9. For example, the intersect (∩) displayed in Figure 9 defines the set of cases that feature both semantic similarity and a direct citation linkage. In general, these are likely communities of well-defined topical domains. Of greater interest to an empirical evaluation of the law as a seamless web, is likely the magnitude and composition of the Citation Only and Semantic Only subsets. Subject to future empirical investigation, we believe the Citation Only components of the graph may represent the exact type of concept exportation to and from particular semantic domains that would indeed make the law a seamless web.”

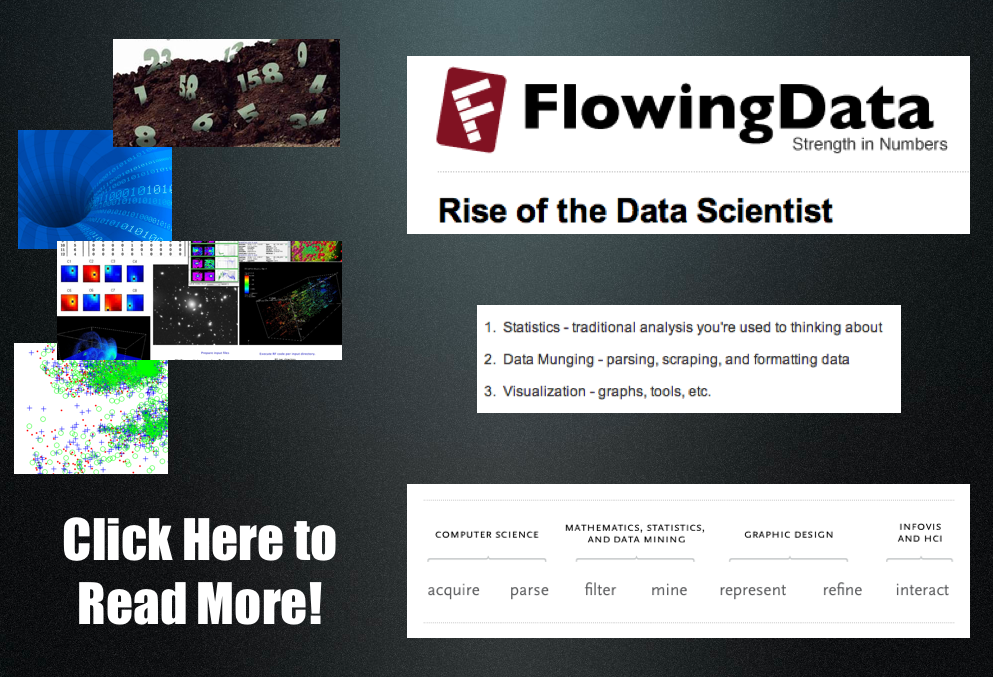

The Rise of the Data Scientist [From Flowing Data]

Earlier in the month, there was a very interesting discussion over at Flowing Data entitled the Rise of the Data Scientist. We decided to highlight it in this post because it raises important issues regarding the relationship between Computational Legal Studies and other movements within law.

As we consider ourselves empiricists, we are strong supporters of the Empirical Legal Studies movement. For those not familiar, the vast majority of existing Empirical Legal studies employ the use of econometric techniques. For some substantive questions, these approaches are perfectly appropriate. While for others, we believe techniques such as network analysis, computational linguistics, etc. are better suited. Even when appropriately employed, as displayed above, we believe the use of traditional statistical approaches should be seen as nested within a larger process. Namely, for a certain class of substantive questions, there exists tremendous amounts of readily available data. Thus, on the front end, the use of computer science techniques such as web scraping and text parsing could help unlock existing large-N data sources thereby improving the quality of inferences collectively produced. On the back end, the use of various methods of information visualization could democratize the scholarship by making the key insights available to a much wider audience.

It is worth noting that our commitment to Computational Legal Studies actually embraces a second important prong. From a mathematical modeling/formal theory perspective, at least for a certain range of questions, agent based models/computational models ≥ closed form analytical models. In other words, we are concerned that many paper & pencil game theoretic models fail to incorporate interactions between components or the underlying heterogeneity of agents. Alternatively, they demonstrate the existence of a P* without concern of whether such an equilibrium is obtained on a timescale of interest. In some instances, these complications do not necessarily matter but in other cases they are deeply consequential.

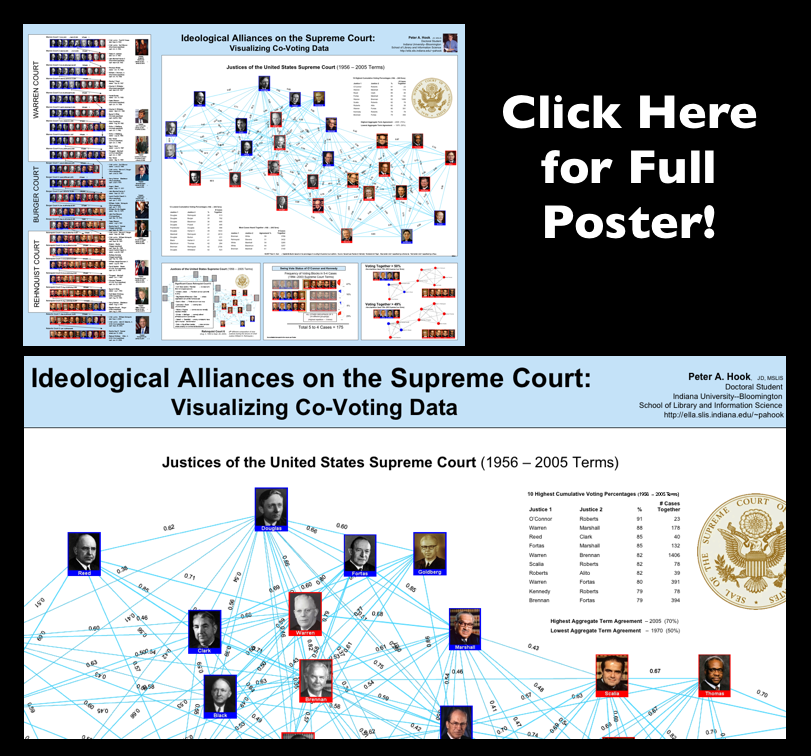

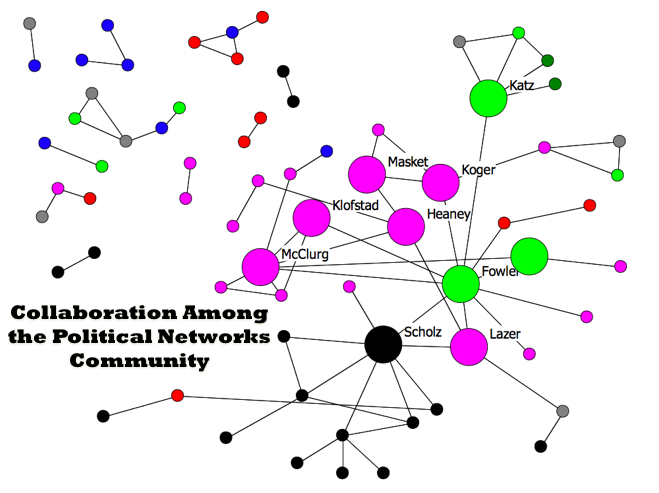

Collaboration Among Political Science Network Scholars

At the recent Networks in Political Science Conference (Harvard 2009), Ramiro Berardo from Arizona presented a paper entitled Networking Networkers: An Exploration of the Patterns of Collaboration among Attendees to the First Harvard Political Networks Conference. The above visual displays the patterns of collaboration among the growing networks community within Political Science. Major scholars in the field including James Fowler, John Scholz, David Lazar and Scott McClurg are displayed. In the northeast corner of the graph you can observe yours truly, Daniel Katz. At the rate he is going, it will not be long until there is a large and central Bommarito node on this graph.

At the recent Networks in Political Science Conference (Harvard 2009), Ramiro Berardo from Arizona presented a paper entitled Networking Networkers: An Exploration of the Patterns of Collaboration among Attendees to the First Harvard Political Networks Conference. The above visual displays the patterns of collaboration among the growing networks community within Political Science. Major scholars in the field including James Fowler, John Scholz, David Lazar and Scott McClurg are displayed. In the northeast corner of the graph you can observe yours truly, Daniel Katz. At the rate he is going, it will not be long until there is a large and central Bommarito node on this graph.

Institutional Rules, Strategic Behavior, Agenda Control & Inferences — Explaining Chief Justice Roberts Anomalous Decision in NAMUNDO

Agenda Control and Careful Inferences

What are the class of potential inferences one should draw when the Chief Justice behaves in a manner which would appear at odds with our prior understandings of his jurisprudence? As I have argued in my previous article Institutional Rules, Strategic Behavior and the Legacy of Chief Justice William Rehnquist: Setting the Record Straight on Dickerson v. United States, there is significant reason to be careful about the class of inferences one draws under conditions similar to those accompanying yesterday’s decision in NAMUNDO v. Holder.

A significant strain of the literature in political science is devoted to studying the power of agenda control. The primary power of Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court is the power of opinion assignment. This includes the right of the Chief to assign to himself the task of opinion writing. Of course, this authority is qualifed as it only applies when he finds himself in the majority coalition. If he finds himself outside of the majority, the Senior Associate Justice in the majority is permitted to exercise this important authority.

The opinion assignment norm provides a significant incentive for the Chief Justice to behave “strategically.” Specifically, in instances where the majority of the court is unwilling to support his preferred outcome, the Chief still has an incentive to join the majority in order to do “damage control.” For example, he can attempt to author a watered-down opinion or an opinion which leaves the major substantive issues for another day.

The Ghost of Dickerson v. United States

Consider as an illustrative example, Justice Rehnquist’s behavior in the 2000 case, Dickerson v. United States. In Dickerson, the Supreme Court was called to consider the ultimate constitutionality of its landmark decision in Miranda v. Arizona. Prior to the Court’s decision, even Miranda’s strongest supporters had expressed significant concern regarding its continued viability. As I sat in the audience on the day of the Dickerson decision, this concern was only heightened when Justice Rehnquist indicated he would deliver the court’s majority opinion.

Chief Justice Rehnquist prior Miranda related jurisprudence indicated a significant hostility to the Court landmark 1966 ruling. In fact, in every decision prior to Miranda he either voted to limit or undercut the Court’s Miranda doctrine. In 57 out of 57 prior cases, the Miranda doctrine had no friend in William Rehnquist. Between his decision in Dickerson and his death, the Rehnquist-led Court considered 5 major Miranda-related cases. In each of these cases, the Chief resumed exactly where he left off prior to Dickerson. He consistently voted to undercut the holding and virtually ignored his own Dickerson opinion.

Chief Justice Rehnquist’s former law clerk, Ted Cruz, writing about the Dickerson decision in a eulogy in the Harvard Law Review, essentially acknowledged the strategic nature of the decision “it was the best that could be gotten from the current members of the Court.” From a doctrinal perspective, his decision was fairly opaque. For example, in responding to questions regarding Dickerson’s logical underpinning Ted Cruz stated, “do not ask why, and please, never, ever, ever cite this opinion for any reason.”

The Strategic Decision in NAMUNDO v. Holder?

Nearly four years after the death of Chief Justice Rehnquist, another socially important decision would be surprisingly authored by a Chief Justice who initially appeared hostile to the question at issue. This time it was Chief Justice John Roberts, a jurist initially socialized in the ways of the high court in the early 1980’s chambers of then Justice William Rehnquist.

In yesterday’s decision in NAMUNDO v. Holder, Chief Justice Roberts authored an 8-1 decision. Leading election law scholars including Professor Rick Hasen have initially described it as “an interpretation of the Act virtually no lawyer thought was plausible.” The lesson from Dickerson and other such cases is strategic behavior on the part of the Chief is always possible. Once it is apparent he does not have the requisite votes to reach his desired policy outcome–what is a strategic Chief Justice to do? Do damage control, limit the core holding or as Professor Gerken has characterized yesterday’s ruling, “punt.”

Law as a Seamless Web? Part II

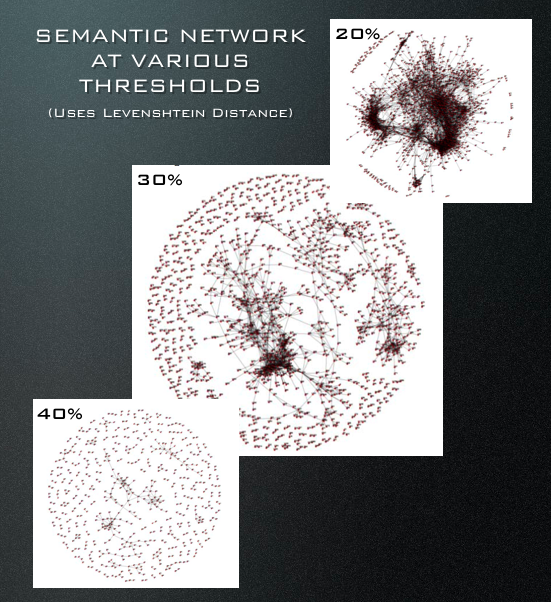

In our paper Law as a Seamless Web, we offer a first-order method to generate case-to-case and opinionunit-to-opinionunit semantic networks. As constructed in the figure above, nodes represent cases decided between 1791-1865 while edges are drawn when two cases possess a certain threshold of semantic similarity. Except for the definition of edges, the process of constructing the semantic graph is identical to that of the citation graph we offered in the prior post. While computer science/computational linguistics offers a variety of possible semantic similarity measures, we choose to employ a commonly used measure. Here a description from the paper:

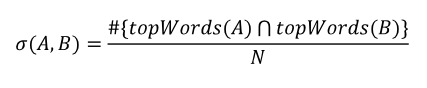

“Semantic similarity measures are the focus of significant work in computational linguistics. Given the scope of the dataset, we have chosen a first-order method for calculating similarity. After lemmatizing the text of the case with WordNet, we store the nouns with the top N frequencies for each case or opinion unit. We define the similarity between two cases or opinion units A and B as the percentage of words that are shared between the top words of A and top words of B.

An edge exists between A and B in the set of edges if σ (A,B) exceeds some threshold. This threshold is the minimum similarity necessary for the graph to represent the presence of a semantic connection.”

An edge exists between A and B in the set of edges if σ (A,B) exceeds some threshold. This threshold is the minimum similarity necessary for the graph to represent the presence of a semantic connection.”

As this a technical paper, it is slanted toward demonstrating proof of methodological concept rather than covering significant substantive ground. With that said, we do offer a hint of our broader substantive goal of detecting the spread of legal concepts between various topical domains. Specifically, with respect to enriching positive political theory, we believe union, intersect and compliment of the semantic and citation networks are really important. More on this point is forthcoming in a subsequent post…

Reading List — Law as a Complex System [Repost from May 15th]

Several months ago, I put together this syllabus for use in a future seminar course Law as a Complex System. This contains far more content than would be practical for the typical 2 credit seminar. However, I have decided to repost this because it could also serve as a reading list for anyone who is interested in learning more about the methodological tradition from which must of our scholarship is drawn. If you see any law related scholarship you believe should be included please feel free to email me.

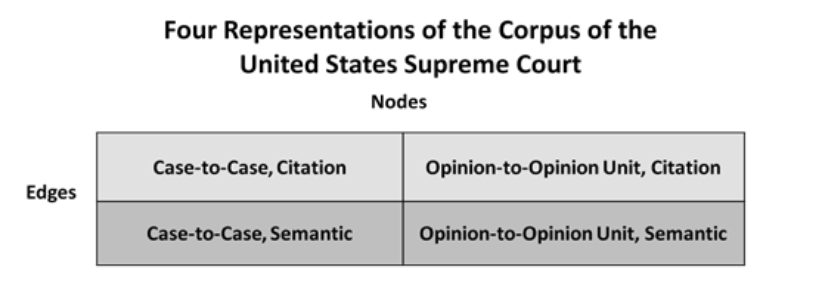

Law as a Seamless Web?

We have recently posted Law as a Seamless Web? Comparison of Various Network Representations of the United States Supreme Court Corpus (1791-2005) to the SSRN. Given this is the first of several posts about the paper, I will speak broadly and leave details for a subsequent post. From the abstract “As research of judicial citation and semantic networks transitions from a strict focus on the structural characteristics of these networks to the evolutionary dynamics behind their growth, it becomes even more important to develop theoretically coherent and empirically grounded ideas about the nature of edges and nodes. In this paper, we move in this direction on several fronts …. Specifically, nodes represent whole cases or individual ‘opinion units’ within cases. Edges represent either citations or semantic connections.” The table below outlines several possible network representations for the USSC corpus.

The goal of the paper is to do some technical and conceptual work. It is a small slice of broader project with James Fowler (UCSD) and James Spriggs (WashU). We recently presented findings from the primary project at the Networks in Political Science Conference. The main project is entitled The Development of Community Structure in the Supreme Court’s Network of Citations and we hope to have a version of this paper on the SSRN soon. In the meantime, we plan additional discussion of Law as a Seamless Web in the days to come.

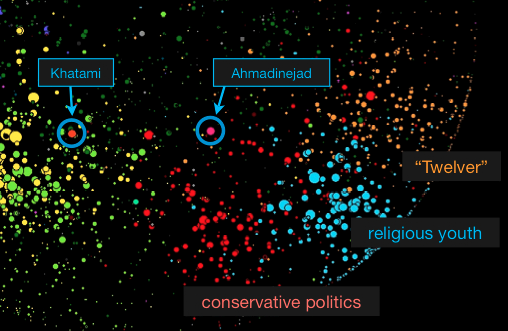

Iranian Blogosphere: Followup from Harvard NIPS 2009

We genuinely enjoyed our trip to Boston for the Networks in Political Science 2009 Conference at Harvard. There were many highlights but given the timely nature of their work we wanted to highlight the presentation by John Kelly & Bruce Etling entitled Mapping Culture, Politics, and Religion in the Arabic Blogosphere. This is a followup to last year’s presentation, Mapping Iran’s Online Public: Politics and Culture in the Persian Blogosphere. As usual, the folks at the Berkman Center are doing great work. Check out today’s New York Times featuring an article entitled Iranian Blogosphere Tests Government’s Limits.

Harvard Political Networks Conference

It was a long trip but we are looking forward to an exciting day of presentations at tomorrow’s Harvard Political Networks Conference. Check out the program! We hope to see you there.