Tag: political science

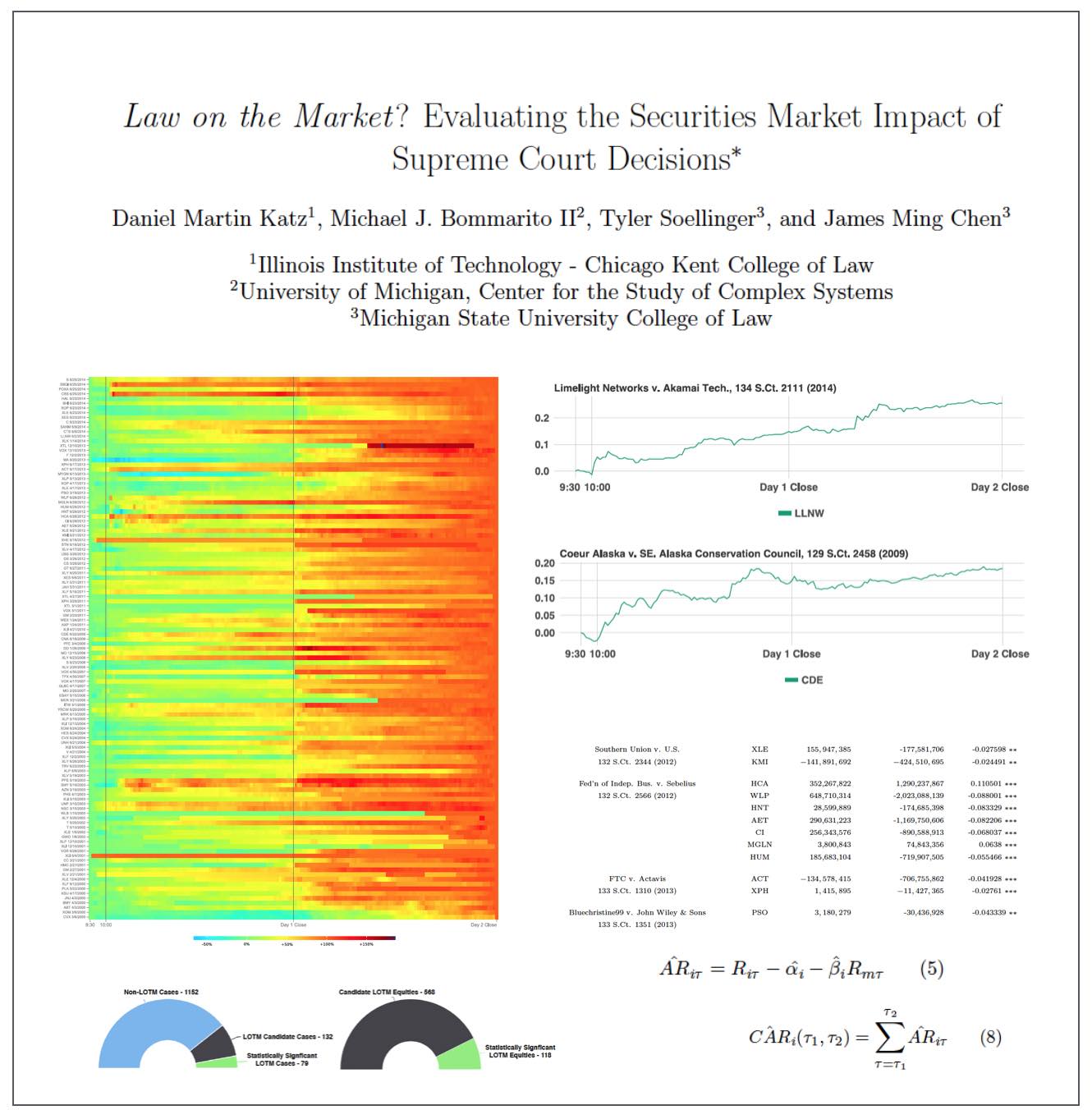

Law on the Market? Evaluating the Securities Market Impact Of Supreme Court Decisions (Katz, Bommarito, Soellinger & Chen)

ABSTRACT: Do judicial decisions affect the securities markets in discernible and perhaps predictable ways? In other words, is there “law on the market” (LOTM)? This is a question that has been raised by commentators, but answered by very few in a systematic and financially rigorous manner. Using intraday data and a multiday event window, this large scale event study seeks to determine the existence, frequency and magnitude of equity market impacts flowing from Supreme Court decisions.

We demonstrate that, while certainly not present in every case, “law on the market” events are fairly common. Across all cases decided by the Supreme Court of the United States between the 1999-2013 terms, we identify 79 cases where the share price of one or more publicly traded company moved in direct response to a Supreme Court decision. In the aggregate, over fifteen years, Supreme Court decisions were responsible for more than 140 billion dollars in absolute changes in wealth. Our analysis not only contributes to our understanding of the political economy of judicial decision making, but also links to the broader set of research exploring the performance in financial markets using event study methods.

We conclude by exploring the informational efficiency of law as a market by highlighting the speed at which information from Supreme Court decisions is assimilated by the market. Relatively speaking, LOTM events have historically exhibited slow rates of information incorporation for affected securities. This implies a market ripe for arbitrage where an event-based trading strategy could be successful.

Available on SSRN and arXiv

Teaching the Complex Systems Course @ University of Michigan ICPSR Summer Program in Quantitative Methods

This upcoming week and next week I have the pleasure of teaching “Complex Systems Models in the Social Sciences” here at the University of Michigan ICPSR Summer Program in Quantitative Methods. The field of complex systems is very diverse and it is difficult to do complete justice to the range of scholarship conducted under this umbrella in a short survey course. However, we strive to cover the canonical topics such as computational game theory and computational modeling, network science, natural language processing, randomness vs. determinism, diffusion, cascades, emergence, empirical approaches to study complexity (including measurement), social epidemiology, non-linear dynamics, etc. Click here or on the image above to access my course materials!

This upcoming week and next week I have the pleasure of teaching “Complex Systems Models in the Social Sciences” here at the University of Michigan ICPSR Summer Program in Quantitative Methods. The field of complex systems is very diverse and it is difficult to do complete justice to the range of scholarship conducted under this umbrella in a short survey course. However, we strive to cover the canonical topics such as computational game theory and computational modeling, network science, natural language processing, randomness vs. determinism, diffusion, cascades, emergence, empirical approaches to study complexity (including measurement), social epidemiology, non-linear dynamics, etc. Click here or on the image above to access my course materials!

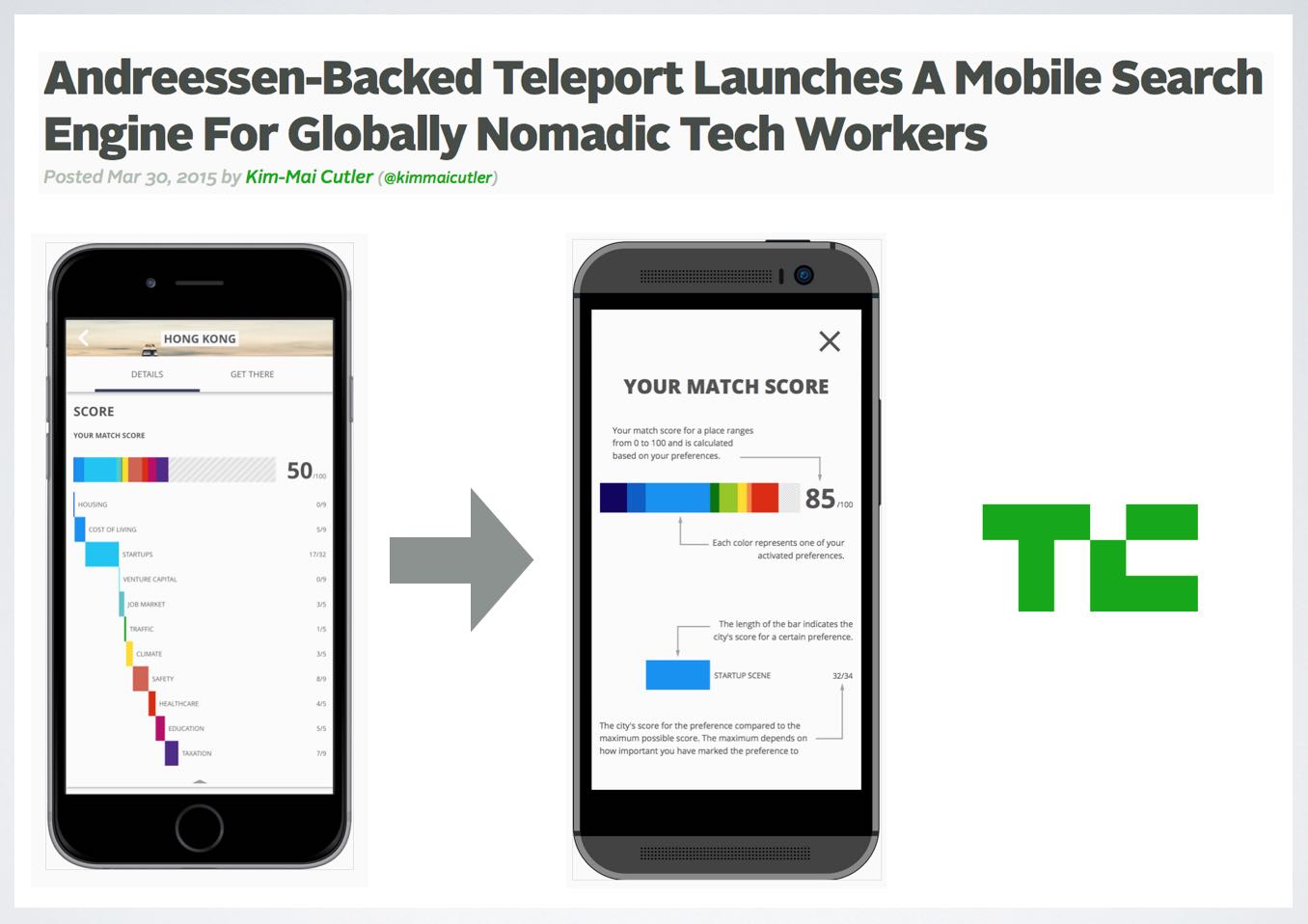

A Mobile Search Engine For Globally Nomadic Tech Workers

Looks like the Tiebout Sorting model — implemented as an app …

Looks like the Tiebout Sorting model — implemented as an app …

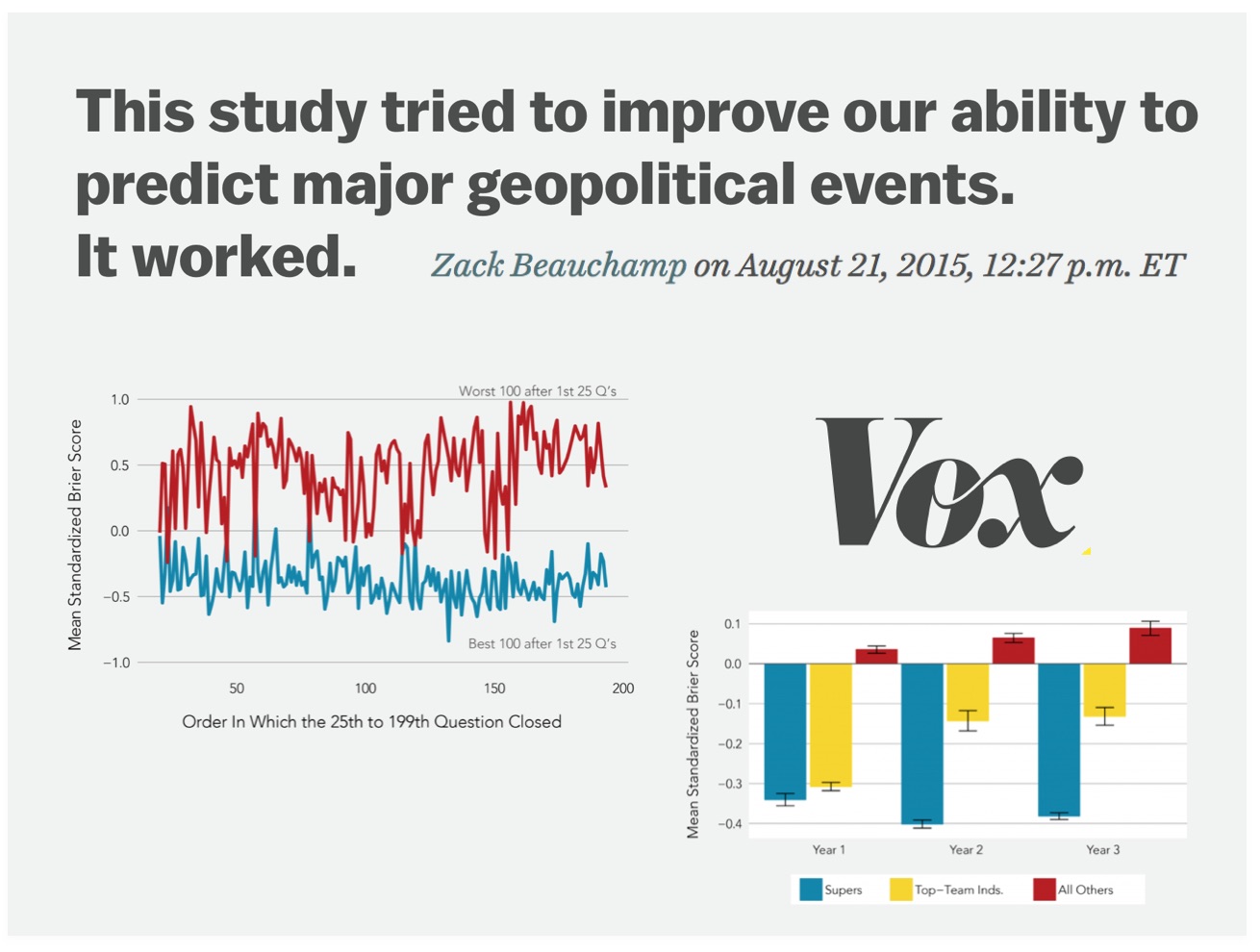

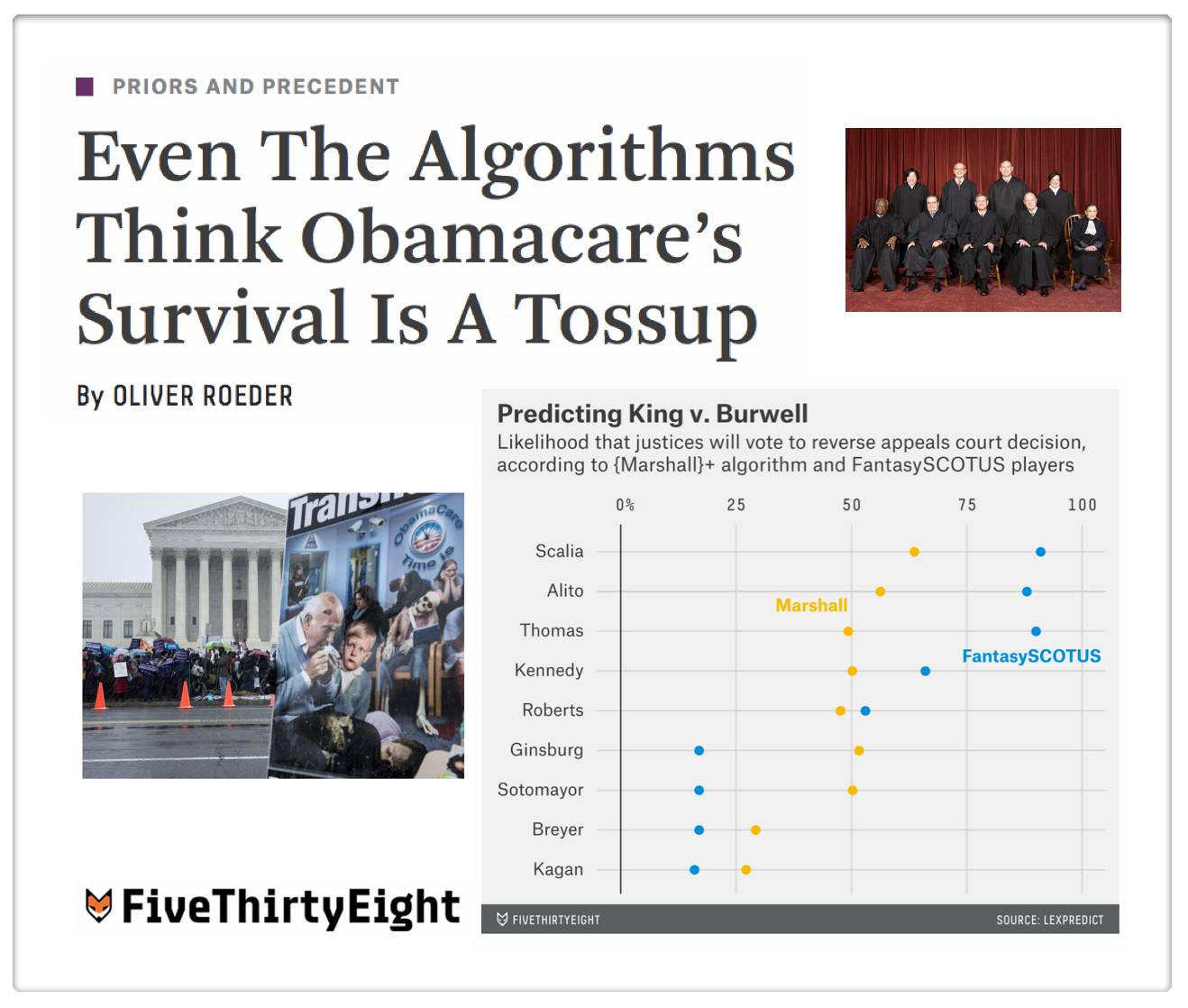

Even The Algorithms Think Obamacare’s Survival Is A Tossup (via 538.com)

Readers will probably observe that {Marshall+} is still a work in progress (for example – my colleague noted {Marshall+} believes that Justice Ginsburg would appear to be slightly more likely to vote to overturn the ACA than Justice Thomas). While this probably will not prove to be correct in King v. Burwell, our method is rigorously backtested and designed to minimize errors across all predictions (not just in this specific case). This optimization question is tricky for the model and it will be the source of future model improvements. I have preached the whole mantra Humans + Machines > Humans or Machines and this problem is a good example. The problem with exclusive reliance upon human experts is they have cognitive biases, info processing issues, etc. The problem with models is that they generate errors that humans would not.

Anyway, the good thing about having a base model such as {Marshall+} is that we can begin to incorporate a range of additional information in an effort to create a {Marshall++} and beyond. And on that front there is more to come …

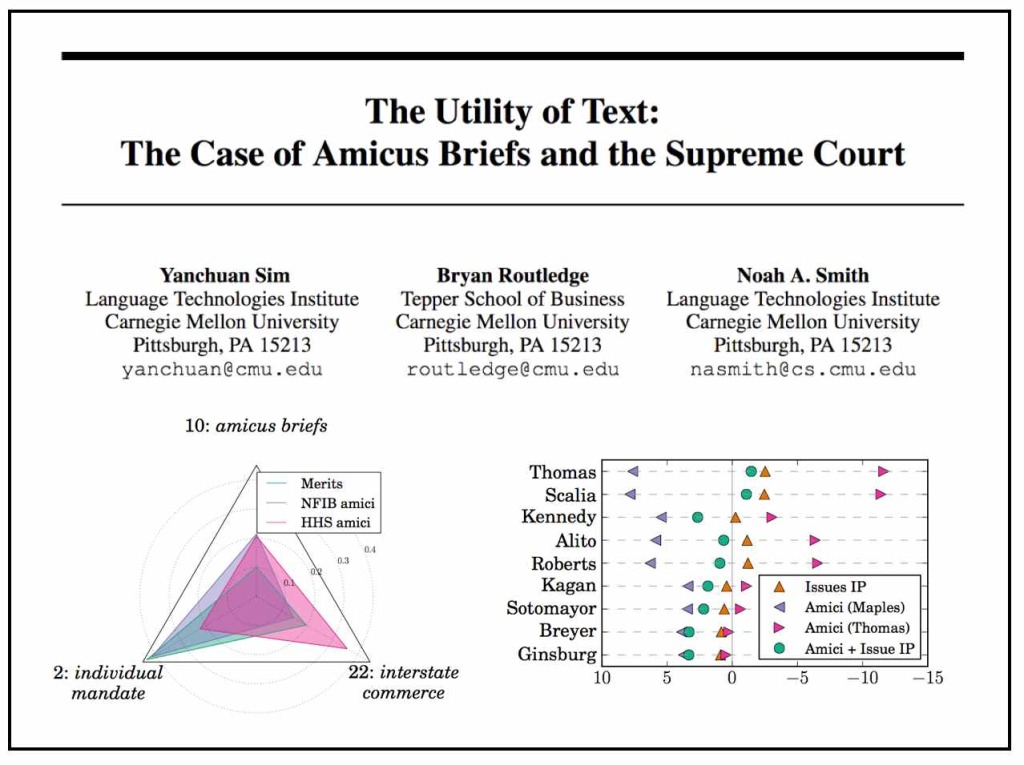

The Utility of Text: The Case of Amicus Briefs and the Supreme Court (by Yanchuan Sim, Bryan Routledge & Noah A. Smith)

From the Abstract: “We explore the idea that authoring a piece of text is an act of maximizing one’s expected utility. To make this idea concrete, we consider the societally important decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States. Extensive past work in quantitative political science provides a framework for empirically modeling the decisions of justices and how they relate to text. We incorporate into such a model texts authored by amici curiae (“friends of the court” separate from the litigants) who seek to weigh in on the decision, then explicitly model their goals in a random utility model. We demonstrate the benefits of this approach in improved vote prediction and the ability to perform counterfactual analysis. (HT: R.C. Richards from Legal Informatics Blog)

From the Abstract: “We explore the idea that authoring a piece of text is an act of maximizing one’s expected utility. To make this idea concrete, we consider the societally important decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States. Extensive past work in quantitative political science provides a framework for empirically modeling the decisions of justices and how they relate to text. We incorporate into such a model texts authored by amici curiae (“friends of the court” separate from the litigants) who seek to weigh in on the decision, then explicitly model their goals in a random utility model. We demonstrate the benefits of this approach in improved vote prediction and the ability to perform counterfactual analysis. (HT: R.C. Richards from Legal Informatics Blog)

This Computer Program Can Predict 7 out of 10 Supreme Court Decisions (via Vox.com)

The story is here. Full form interview with Mike + Josh is here. (I unfortunately could not participate because I was teaching my ICPSR class). Our paper is available on SSRN and on the physics arXiv.

The story is here. Full form interview with Mike + Josh is here. (I unfortunately could not participate because I was teaching my ICPSR class). Our paper is available on SSRN and on the physics arXiv.

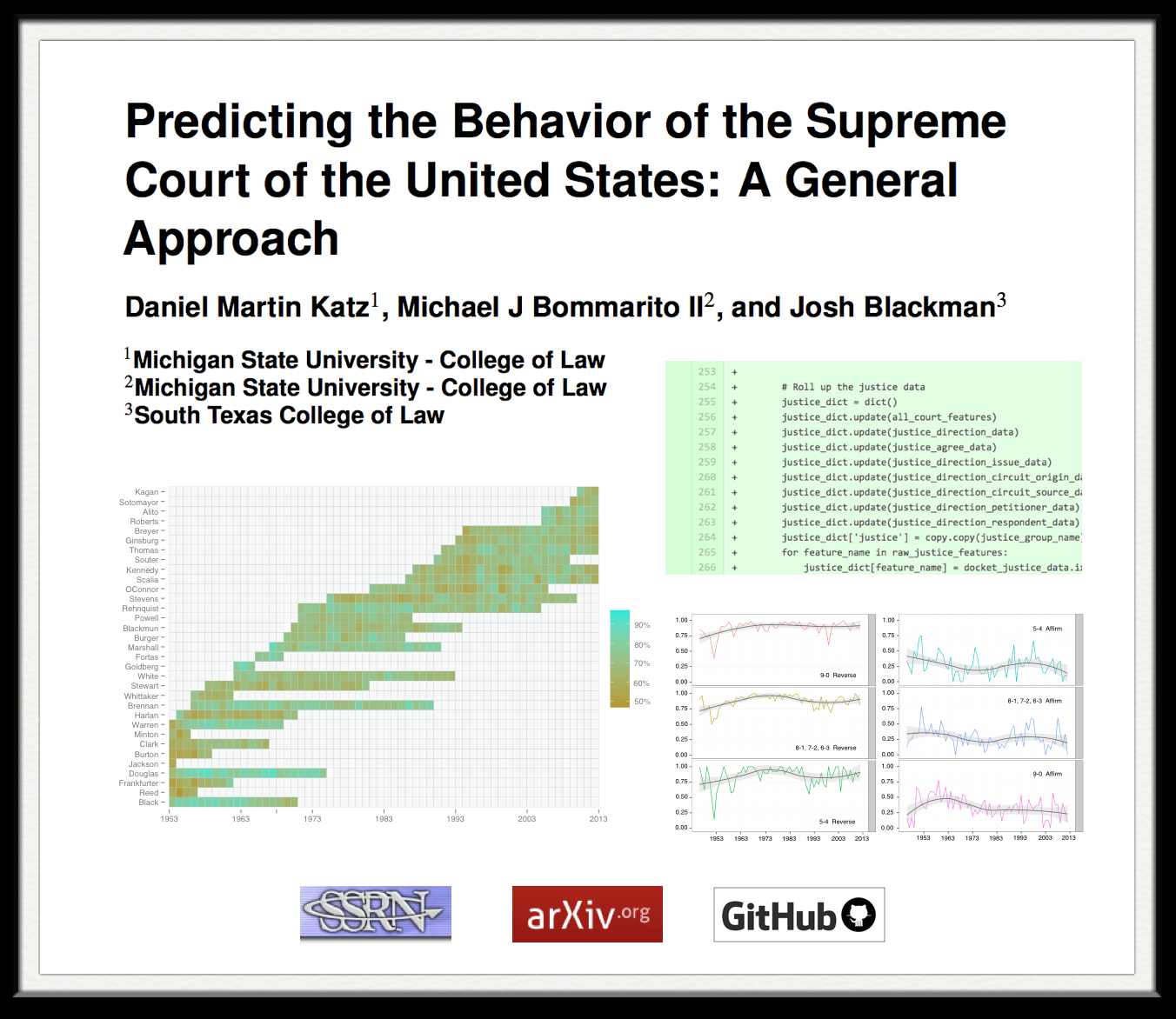

Predicting the Behavior of the Supreme Court of the United States: A General Approach (Katz, Bommarito & Blackman)

Abstract: “Building upon developments in theoretical and applied machine learning, as well as the efforts of various scholars including Guimera and Sales-Pardo (2011), Ruger et al. (2004), and Martin et al. (2004), we construct a model designed to predict the voting behavior of the Supreme Court of the United States. Using the extremely randomized tree method first proposed in Geurts, et al. (2006), a method similar to the random forest approach developed in Breiman (2001), as well as novel feature engineering, we predict more than sixty years of decisions by the Supreme Court of the United States (1953-2013). Using only data available prior to the date of decision, our model correctly identifies 69.7% of the Court’s overall affirm and reverse decisions and correctly forecasts 70.9% of the votes of individual justices across 7,700 cases and more than 68,000 justice votes. Our performance is consistent with the general level of prediction offered by prior scholars. However, our model is distinctive as it is the first robust, generalized, and fully predictive model of Supreme Court voting behavior offered to date. Our model predicts six decades of behavior of thirty Justices appointed by thirteen Presidents. With a more sound methodological foundation, our results represent a major advance for the science of quantitative legal prediction and portend a range of other potential applications, such as those described in Katz (2013).”

You can access the current draft of the paper via SSRN or via the physics arXiv. Full code is publicly available on Github. See also the LexPredict site. More on this to come soon …

Teaching the Complex Systems Course @ University of Michigan ICPSR Summer Program in Quantitative Methods

This upcoming week and next week I have the pleasure of teaching “Complex Systems Models in the Social Sciences” here at the University of Michigan ICPSR Summer Program in Quantitative Methods. The field of complex systems is very diverse and it is difficult to do complete justice to the range of scholarship conducted under this umbrella in a short survey course. However, we strive to cover the canonical topics such as computational game theory and computational modeling, network science, natural language processing, randomness vs. determinism, diffusion, cascades, emergence, empirical approaches to study complexity (including measurement), social epidemiology, non-linear dynamics, etc. Click here or on the image above to access my course materials!

This upcoming week and next week I have the pleasure of teaching “Complex Systems Models in the Social Sciences” here at the University of Michigan ICPSR Summer Program in Quantitative Methods. The field of complex systems is very diverse and it is difficult to do complete justice to the range of scholarship conducted under this umbrella in a short survey course. However, we strive to cover the canonical topics such as computational game theory and computational modeling, network science, natural language processing, randomness vs. determinism, diffusion, cascades, emergence, empirical approaches to study complexity (including measurement), social epidemiology, non-linear dynamics, etc. Click here or on the image above to access my course materials!

Network Analysis and the Law — 3D-Hi-Def Visualization of the Time Evolving Citation Network of the United States Supreme Court

What are some of the key takeaway points?

(1) The Supreme Court’s increasing reliance upon its own decisions over the 1800-1830 window.

(2) The important role of maritime/admiralty law in the early years of the Supreme Court’s citation network. At least with respect to the Supreme Court’s citation network, these maritime decisions are the root of the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence.

(3) The increasing centrality of decisions such as Marbury v. Madison, Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee to the overall network.

The Development of Structure in the SCOTUS Citation Network

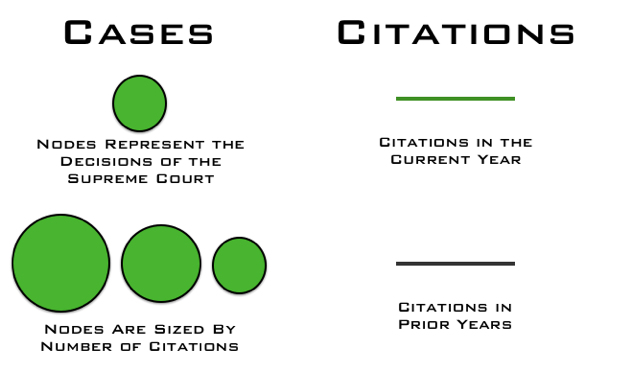

The visualization offered above is the largest weakly connected component of the citation network of the United States Supreme Court (1800-1829). Each time slice visualizes the aggregate network as of the year in question.

In our paper entitled Distance Measures for Dynamic Citation Networks, we offer some thoughts on the early SCOTUS citation network. In reviewing the visual above note ….“[T]he Court’s early citation practices indicate a general absence of references to its own prior decisions. While the court did invoke well-established legal concepts, those concepts were often originally developed in alternative domains or jurisdictions. At some level, the lack of self-reference and corresponding reliance upon external sources is not terribly surprising. Namely, there often did not exist a set of established Supreme Court precedents for the class of disputes which reached the high court. Thus, it was necessary for the jurisprudence of the United States Supreme Court, seen through the prism of its case-to-case citation network, to transition through a loading phase. During this loading phase, the largest weakly connected component of the graph generally lacked any meaningful clustering. However, this sparsely connected graph would soon give way, and by the early 1820’s, the largest weakly connected component displayed detectable structure.”

What are the elements of the network?

What are the labels?

To help orient the end-user, the visualization highlights several important decisions of the United States Supreme Court offered within the relevant time period:

Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803) we labeled as ”Marbury”

Murray v. The Charming Betsey, 6 U.S. 64 (1804) we labeled as “Charming Betsey” Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee, 14 U.S. 304 (1816) we labeled as “Martin’s Lessee”

The Anna Maria, 15 U.S. 327 (1817) we labeled as “Anna Maria”

McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. 316 (1819) we labeled as “McCulloch”

Why do cases not always enter the visualization when they are decided?

As we are interested in the core set of cases, we are only visualizing the largest weakly connected component of the United States Supreme Court citation network. Cases are not added until they are linked to the LWCC. For example, Marbury v. Madison is not added to the visualization until a few years after it is decided.

How do I best view the visualization?

Given this is a high-definition video, it may take few seconds to load. We believe that it is worth the wait. In our view, the video is best consumed (1) Full Screen (2) HD On (3) Scaling Off.

Where can I find related papers?

Here is a non-exhaustive list of related scholarship:

Daniel Martin Katz, Network Analysis Reveals the Structural Position of Foreign Law in the Early Jurisprudence of the United States Supreme Court (Working Paper – 2014)

Yonatan Lupu & James H. Fowler, Strategic Citations to Precedent on the U.S. Supreme Court, 42 Journal of Legal Studies 151 (2013)

Michael Bommarito, Daniel Martin Katz, Jon Zelner & James Fowler, Distance Measures for Dynamic Citation Networks, 389 Physica A 4201 (2010).

Michael Bommarito, Daniel Martin Katz & Jon Zelner, Law as a Seamless Web? Comparison of Various Network Representations of the United States Supreme Court Corpus (1791-2005) in Proceedings of the 12th Intl. Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Law (2009).

Frank Cross, Thomas Smith & Antonio Tomarchio, The Reagan Revolution in the Network of Law, 57 Emory L. J. 1227 (2008).

James Fowler & Sangick Jeon, The Authority of Supreme Court Precedent, 30 Soc. Networks 16 (2008).

Elizabeth Leicht, Gavin Clarkson, Kerby Shedden & Mark Newman, Large-Scale Structure of Time Evolving Citation Networks, 59 European Physics Journal B 75 (2007).

Thomas Smith, The Web of the Law, 44 San Diego L.R. 309 (2007).

James Fowler, Timothy R. Johnson, James F. Spriggs II, Sangick Jeon & Paul J. Wahlbeck, Network Analysis and the Law: Measuring the Legal Importance of Precedents at the U.S. Supreme Court, 15 Political Analysis, 324 (2007).

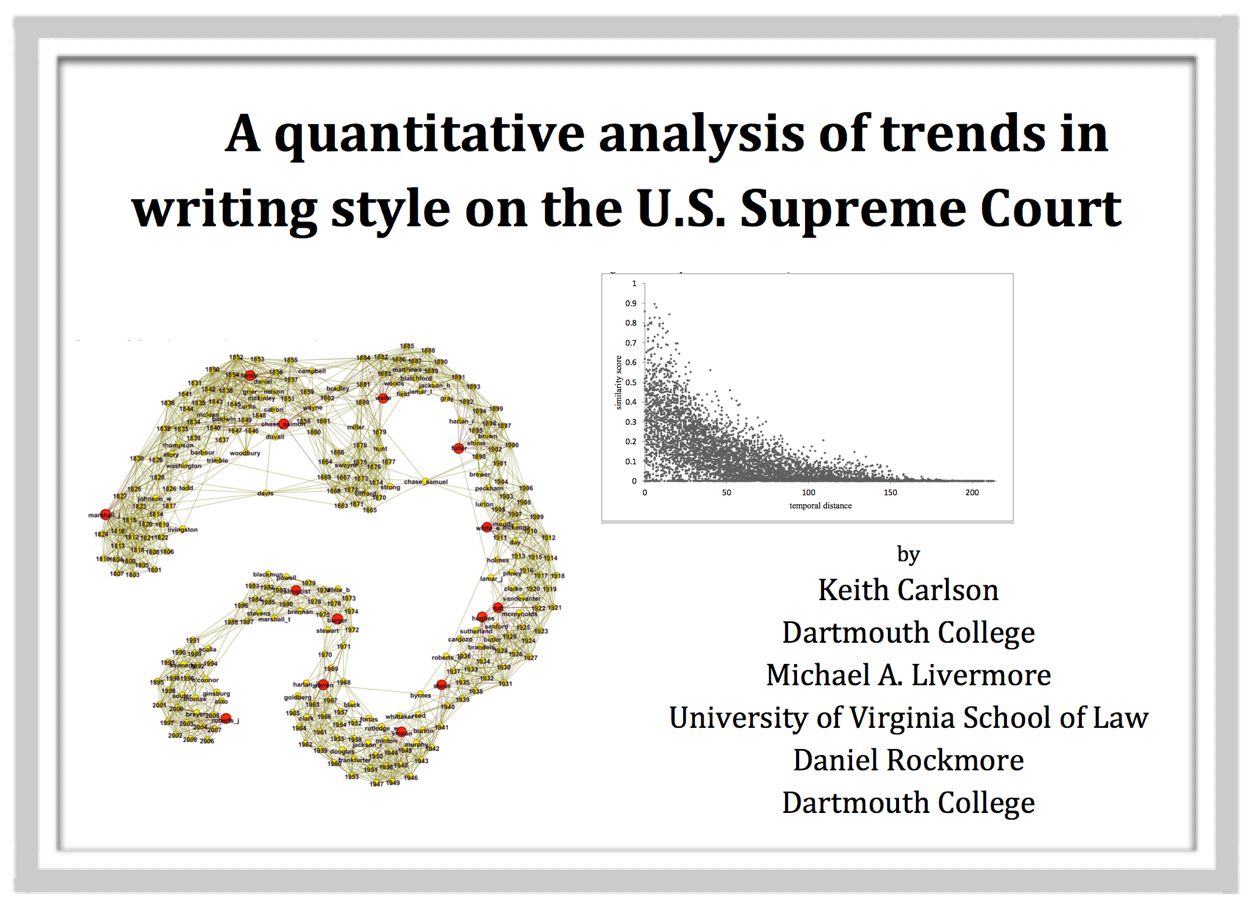

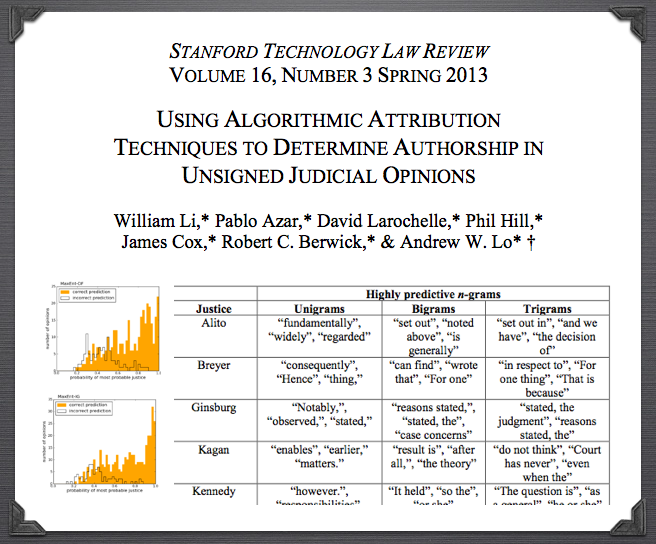

Using Algorithmic Attribution Techniques to Determine Authorship In Unsigned Judicial Opinions

From the Abstract: “This Article proposes a novel and provocative analysis of judicial opinions that are published without indicating individual authorship. Our approach provides an unbiased, quantitative, and computer scientific answer to a problem that has long plagued legal commentators. Our work uses natural language processing to predict authorship of judicial opinions that are unsigned or whose attribution is disputed. Using a dataset of Supreme Court opinions with known authorship, we identify key words and phrases that can, to a high degree of accuracy, predict authorship. Thus, our method makes accessible an important class of cases heretofore inaccessible. For illustrative purposes, we explain our process as applied to the Obamacare decision, in which the authorship of a joint dissent was subject to significant popular speculation. We conclude with a chart predicting the author of every unsigned per curiam opinion during the Roberts Court.” <HT: Josh Blackman>