Month: January 2011

Modeling the Financial Crisis [ From Nature ]

This week’s issue of Nature offers two brief but meaningful articles on the financial crisis. Here are the abstracts:

Financial Systems: Ecology and Economics (By Neil Johnson & Thomas Lux): “In the run-up to the recent financial crisis, an increasingly elaborate set of financial instruments emerged, intended to optimize returns to individual institutions with seemingly minimal risk. Essentially no attention was given to their possible effects on the stability of the system as a whole. Drawing analogies with the dynamics of ecological food webs and with networks within which infectious diseases spread, we explore the interplay between complexity and stability in deliberately simplified models of financial networks. We suggest some policy lessons that can be drawn from such models, with the explicit aim of minimizing systemic risk.”

Systemic Risk in Banking Ecosystems (By Andrew G. Haldane & Robert M. May): “In the run-up to the recent financial crisis, an increasingly elaborate set of financial instruments emerged, intended to optimize returns to individual institutions with seemingly minimal risk. Essentially no attention was given to their possible effects on the stability of the system as a whole. Drawing analogies with the dynamics of ecological food webs and with networks within which infectious diseases spread, we explore the interplay between complexity and stability in deliberately simplified models of financial networks. We suggest some policy lessons that can be drawn from such models, with the explicit aim of minimizing systemic risk.”

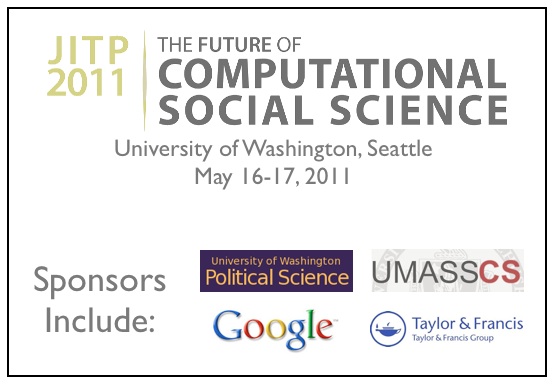

The Future of Computational Social Science @ University of Washington – Submissions Due Jan. 30, 2011

As a member of the conference program committee, I would like encourage you to consider submitting a paper to “The Future of Computational Social Science” at the University of Washington – Seattle, May 16-17, 2011. The conference aims to bring together leaders from industry and the academy to present cutting edge work. For those who might be interested in attending, please click on the image above or here to access the call for papers. Here is an excerpt:

As a member of the conference program committee, I would like encourage you to consider submitting a paper to “The Future of Computational Social Science” at the University of Washington – Seattle, May 16-17, 2011. The conference aims to bring together leaders from industry and the academy to present cutting edge work. For those who might be interested in attending, please click on the image above or here to access the call for papers. Here is an excerpt:

“Computational social science is an emergent field and source of new theoretical and methodological innovation for social science more broadly. Multidisciplinary teams of social and computer scientists are increasingly common in the lab and at workshops where cross-fertilization occurs in the areas of theory, data, methods, and tools. Peer-reviewed interdisciplinary work is becoming more common as the computational tools and techniques of computer science are being used by social scientists. Previously, large-scale computational processing was the purview of expensive, university-centric computing labs. Now, with the democratization of technology, universities and for-profit firms increasingly provide large amounts of inexpensive computing power to researchers and citizens alike.”

Authors are invited to prepare and submit to JITP a research paper, policy viewpoint, workbench note, or teaching innovation manuscript by January 30, 2011. There is also an option to submit an abstract for potential inclusion in the poster session. The poster abstract is also due January 30, 2011.

Yesterday’s Fast is Today’s Slow – The 2011 Season Starts Today!

Well my Ducks did not quite get it done last night in the BCS National Championship Game. Despite the loss, I think that it is important to emphasize that innovation on a variety of fronts is responsible for bringing Oregon to the title game. Simply put, Oregon has redefined the game and there is no doubt that copycats will soon begin to follow their model. The Ducks still have one more big step to take but they will be one of the favorites in 2011 — that season begins today.

The AI Revolution Is On [ Via Wired Magazine ]

From the Full Article: “AI researchers began to devise a raft of new techniques that were decidedly not modeled on human intelligence. By using probability-based algorithms to derive meaning from huge amounts of data, researchers discovered that they didn’t need to teach a computer how to accomplish a task; they could just show it what people did and let the machine figure out how to emulate that behavior under similar circumstances. … They don’t possess anything like human intelligence and certainly couldn’t pass a Turing test. But they represent a new forefront in the field of artificial intelligence. Today’s AI doesn’t try to re-create the brain. Instead, it uses machine learning, massive data sets, sophisticated sensors, and clever algorithms to master discrete tasks. Examples can be found everywhere …”

Humanities in the Digital Age [Via MIT World]

About the Lecture: “Reports of the demise of the humanities are exaggerated, suggest these panelists, but there may be reason to fear its loss of relevance. Three scholars whose work touches a variety of disciplines and with wide knowledge of the worlds of academia and publishing ponder the meaning and mission of the humanities in the digital age. Getting a handle on the term itself proves somewhat elusive. Alison Byerly invokes those fields involved with “pondering the deep questions of humanity,” such as languages, the arts, literature, philosophy and religion. Steven Pinker boils it down to “the study of the products of the human mind.” Moderator David Thorburn wonders if the humanities are those endeavors that rely on interpretive rather than empirical research, but both panelists vigorously make the case that the liberal arts offer increasing opportunities for data-based analysis.

Technology is opening up new avenues for humanities scholars. In general, Byerly notes, humanities “tend to privilege individual texts or products of the human mind, rather than collective wisdom or data.” More recently, online collections or data bases of text, art and music make possible wholly different frameworks for study.

Humanists are adopting new tools and methods for teaching and publishing as well. As Pinker notes, the process for publishing articles in scholarly journals remains painfully slow: in experimental psychology, a “six year lag from having an idea to seeing it in print.” He suggests a “second look” at the process of peer review, perhaps publishing everything online, “and stuff that’s crummy sinks to the bottom as no one links to or reads it.” Pinker looks forward to a future where he no longer has to spend a “lot of time leafing through thick books” looking for text strings, or flipping to and from footnotes. “We could love books as much as we always have, but not necessarily confine ourselves to their limitations, which are just historical artifacts,” he says.”