Three Takeaways

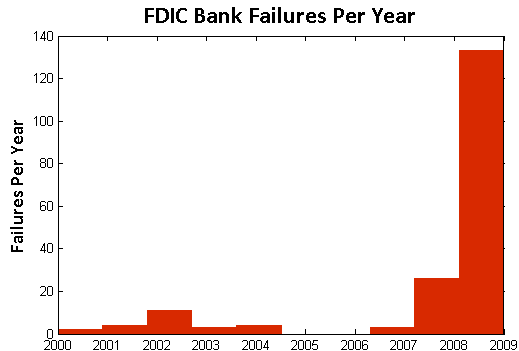

- Acceleration: There were four failures in the first six months of 2008, followed by another 22 failures in the next six months. By January of 2009, there were 21 failures in the first three months of the year, followed by 138 from April to last Friday.

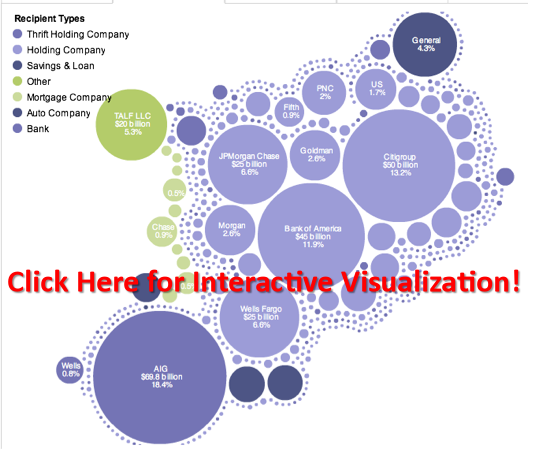

- Magnitude: Failures in the past two years have cost the Depositors Insurance Fund an estimated $57B. The IndyMac failure of July 2008 accounted for $10B alone, followed by BankUnited at $4.9B and Guaranty Banks at $3B.

- Spatial Correlation: There is a significant amount of spatial correlation in California, Georgia, Florida, Texas, and Illinois. These states account for 77% of the total costs to the Depositors Insurance Fund. Furthermore, most of the losses in California and Georgia were concentrated highly around a few urban centers.

The Movie

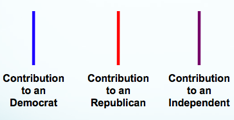

The movie below shows the location of bank failures, beginning in 2008 and concluding with the three failed banks from Friday, December 11, 2009. Each green circle corresponds to a bank failure, and the size of each circle corresponds logarithmically to the FDIC’s estimated cost for the Depository Insurance Fund, as stated in the FDIC press releases. For failures with joint press releases, such as the 9 banks that failed on October 30th, the circles are sized in proportion to their relative total deposits.

Our visualization is similar to this one offered by the Wall Street Journal. For sizing the circles, the WSJ relied upon the value of assets at the time of failure. By contrast, our approach focuses upon the estimated impact to the Depositors Insurance Fund (DIF). In several instances, this alternative approach leads to a different qualitative result than the WSJ. For example, consider the case of Washington Mutual. While many have characterized Washington Mutual’s failure as the largest in history, according to the FDIC press release the failure did not actually lead to a draw upon Depositors Insurance Fund. By contrast, the FDIC estimated cost for the IndyMac Bank failure was substantial– the latest available estimate sets it at 10.7 billion.

Additional Background

As reported in a number of news outlets, Friday witnessed the failure of three more banks – Solutions Bank (Overland Park, KS), Valley Capital Bank (Mesa, AZ), and Republic Federal Bank (Miami, FL).

According to information obtained from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), there have been a total of 186 bank failures in the United States since 2000. Of these, 159 banks or roughly 85% have occurred in the past two years. The plot below displays the yearly failures since 2000. These 159 failures over the past two years have cost the Depositors Insurance Fund an estimated $57B.

In addition to the increase in the rate of bank failures, there has also been a substantial amount of spatial correlation between these failures. The table below shows the five states with the highest estimated total costs to the Depositors Insurance Fund since 2008. Together, these five states account for $44B of the total $57B in the past two years.

| State | Estimated Cost to Fund |

| California | $19.33B |

| Georgia | $9.29B |

| Florida | $6.77B |

| Texas | $4.56B |

| Illinois | $4.12B |